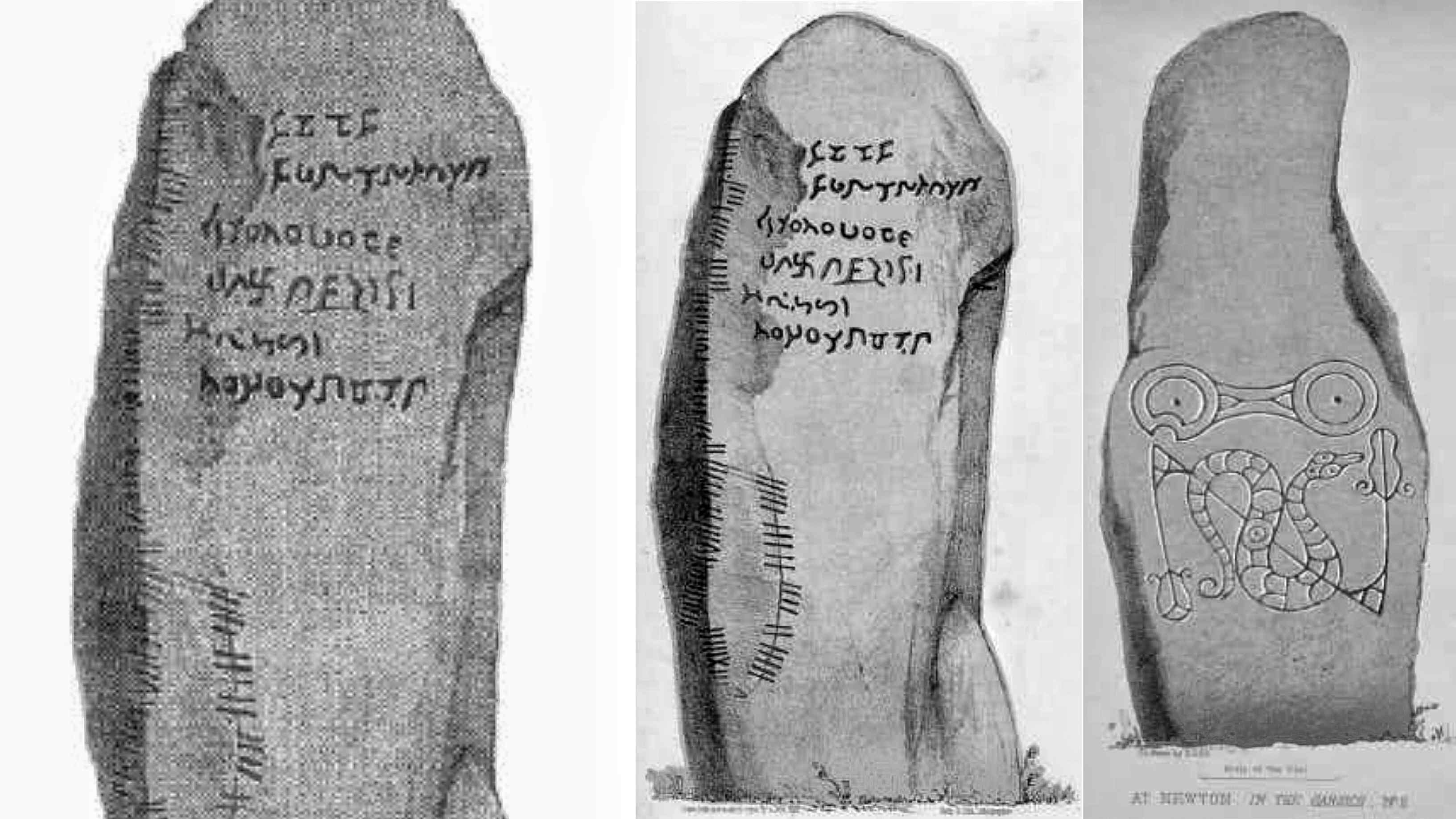

Every once in a while, interesting things come across my desk beyond our understanding. The mysterious Newton Stone is one of these artifacts. This ancient monolith has a carved message written in a mysterious language that hasn’t been solved yet, and the writing can be read using at least five different ancient alphabets.

Uncovering the Newton Stone

In 1804 the Earl of Aberdeen, George Hamilton-Gordon, was building a road near Pitmachie Farm in Aberdeenshire. The mysterious megalith was found there, and the Scottish archaeologist Alexander Gordon later moved it to the garden of Newton House in the Parish of Culsalmond, around a mile north of Pitmachie Farm. The Newton Stone is described as follows by the Aberdeenshire Council of Newton House:

Unknown script

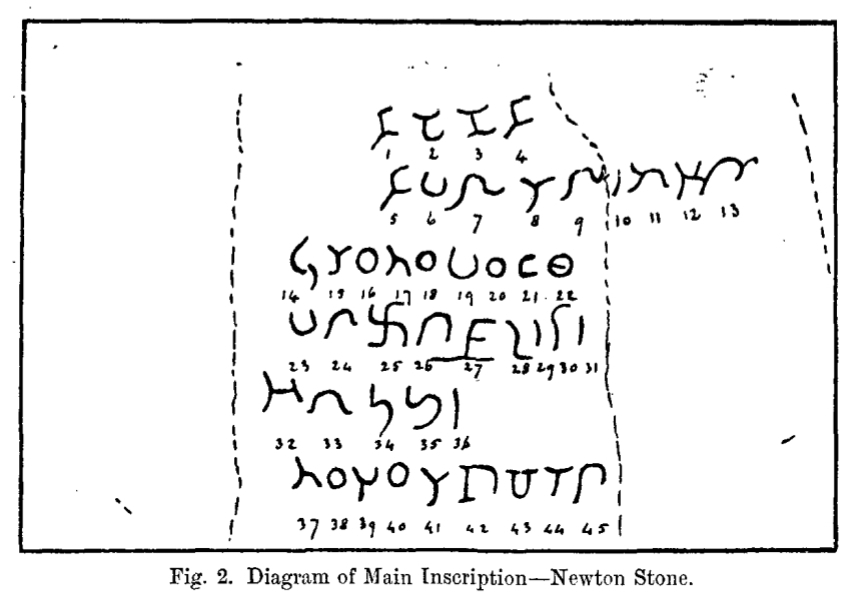

The early Irish language was written with the Ogham alphabet between the 1st and 9th centuries. The short row of writing on the Newton Stone is spread across the top third of the stone. It has six lines with 48 characters and symbols, including a swastika. Academics have never figured out what language to write this message, so it is called the unknown script.

Most experts agree that long Ogham’s writing is from long ago. For example, the unknown inscription was thought to be from the 9th century by the Scottish historian William Forbes Skene. Nonetheless, several historians assert that the short row was added to the stone in the late eighteenth or early 19th century, implying that the mysterious unknown script is a recent hoax or a poorly done forgery.

Deciphering the Stone

John Pinkerton first wrote about the mysterious engravings on the Newton Stone in his 1814 book Inquiry into the Story of Scotland, but he didn’t try to figure out what the “unknown script” said.

In 1822, John Stuart, a professor of Greek at Marischal College, wrote a paper called Sculpture Pillars in the Northern Part of Scotland for the Edinburgh Society of Antiquaries. In it, he talked about a translation attempt by Charles Vallancey, who thought the characters were Latin.

Dr. William Hodge Mill (1792–1853) was an English churchman and orientalist, the first head of Bishop’s College, Calcutta, and afterward Regius Professor of Hebrew at Cambridge. In 1856, Stuart issued Sculptured Stones of Scotland, which described Mill’s work.

Dr. Mills said that the unknown script was Phoenician. Because he was so well-known in the field of ancient languages, people took his opinion seriously. They talked about it a lot, especially at a gathering of the British Association in Cambridge, England, in 1862.

Even though Dr. Mill died in 1853, his paper On the Decipherment of the Phoenician Inscribed on the Newton Stone was found in Aberdeenshire, and his transformation of the unknown script was read during this debate. Several scholars agreed with Mill that the script was written in Phoenicians. For example, Dr. Nathan Davis discovered Carthage, and Prof Aufrecht thought the script was written in Phoenician.

But Mr. Thomas Wright, a skeptic, suggested a simpler translation in debased Latin: Hie iacet Constantinus Here is where the son of is buried. Mr. Vaux of the British Museum approved it as medieval Latin. The palaeographer Constantine Simonides also agreed with Wright’s translation, but he changed the Latin to Greek.

Three years after this disaster, in 1865, the antiquarian Alexander Thomson gave a talk to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in which he talked about the five most popular theories about how to decipher the code:

- Phoenician (Nathan Davis, Theodor Aufrecht, and William Mills);

- Latin (Thomas Wright and William Vaux);

- Gnostic symbolism (John O. Westwood)

- Greek (Constantine Simonides)

- Gaelic (a Thomson correspondent who did not want to be named);

Fringe theories abound!

While this group of experts argued about what the inscription on the Newton Stone meant and which of the five possible languages was used to write the cryptic message, a different group of more unusual researchers kept coming up with new ideas. For example, Mr. George Moore suggested translating it into Hebrew-Bactrian, while others compared it to Sinaitic, an old Canaanite language.

Lieutenant Colonel Laurence Austine Waddell used to be a British explorer, professor of Tibetan, chemistry, and pathology, and an amateur archaeologist researching Sumerian and Sanskrit. In 1924, Waddell published his ideas about Out of India, which included a radical new way to read the language called Hitto-Phoenician.

Waddell’s controversial books about the history of civilization were very popular with the public. Today, some people consider him the real-life inspiration for the fictional archaeologist Indiana Jones, but his work earned him little respect as a serious Assyriologist.

ipari

Today, many theories try to figure out what the mysterious message on the Newton Stone means. Some of these theories are debased Latin, medieval Latin, Greek, Gaelic, Gnostic symbolism, Hebrew-Bactrian, Hitto-Phoenician, Sinaitic, and Old Irish. However, these ideas have yet to be proven to be correct. This weekend, you should give the Newton Stone an hour since it wouldn’t be the first time an outsider found a key to an old problem.