E moni e Eseta o le Eseta is best known as the site of the mysterious and majestic moai statues, but these are not the only wonders that the South Pacific island has to offer. While the moai structures are fascinating because of their unknown purpose and enigmatic artisans, the island’s extinct language of “Rongorongo” is equally puzzling. The one-of-a-kind written language appears to be evident out of nowhere in the 1700s, yet it was deported to obscurity in less than two centuries.

It is believed that the Polynesian people migrated to what is now known as Easter Island somewhere between 300 AD and 1200 AD, and established themselves there. Because of overpopulation and overexploitation of their resources, the Polynesians experienced a population fall after an initially flourishing civilization. It is said that when European explorers arrived in 1722, they brought diseases with them that severely depleted their population.

The name Easter Island was given by the island’s first recorded European visitor, the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen, who encountered it on Easter Sunday, 5th of April, in 1722, while searching for “Davis Land.” Roggeveen named it Paasch-Eyland (18th-century Dutch for “Easter Island”). The island’s official Spanish name, Isla de Pascua, also means “Easter Island.”

The Rongorongo glyphs were discovered in 1869 quite accidentally. One of these texts was given to the Bishop of Tahiti as an unusual gift. When Eugène Eyraud, a lay friar of the Roman Catholic Church, arrived on Easter Island as a missionary on January 2, 1864, he made the discovery of the Rongorongo writing for the first time. In a written description of his visit, he described his finding of twenty-six wooden tablets with the following strange writing on them.

“In every hut one finds wooden tablets or sticks covered in several sorts of hieroglyphic characters: They are depictions of animals unknown on the island, which the natives draw with sharp stones. Each figure has its own name; but the scant attention they pay to these tablets leads me to think that these characters, remnants of some primitive writing, are now for them a habitual practice which they keep without seeking its meaning.”

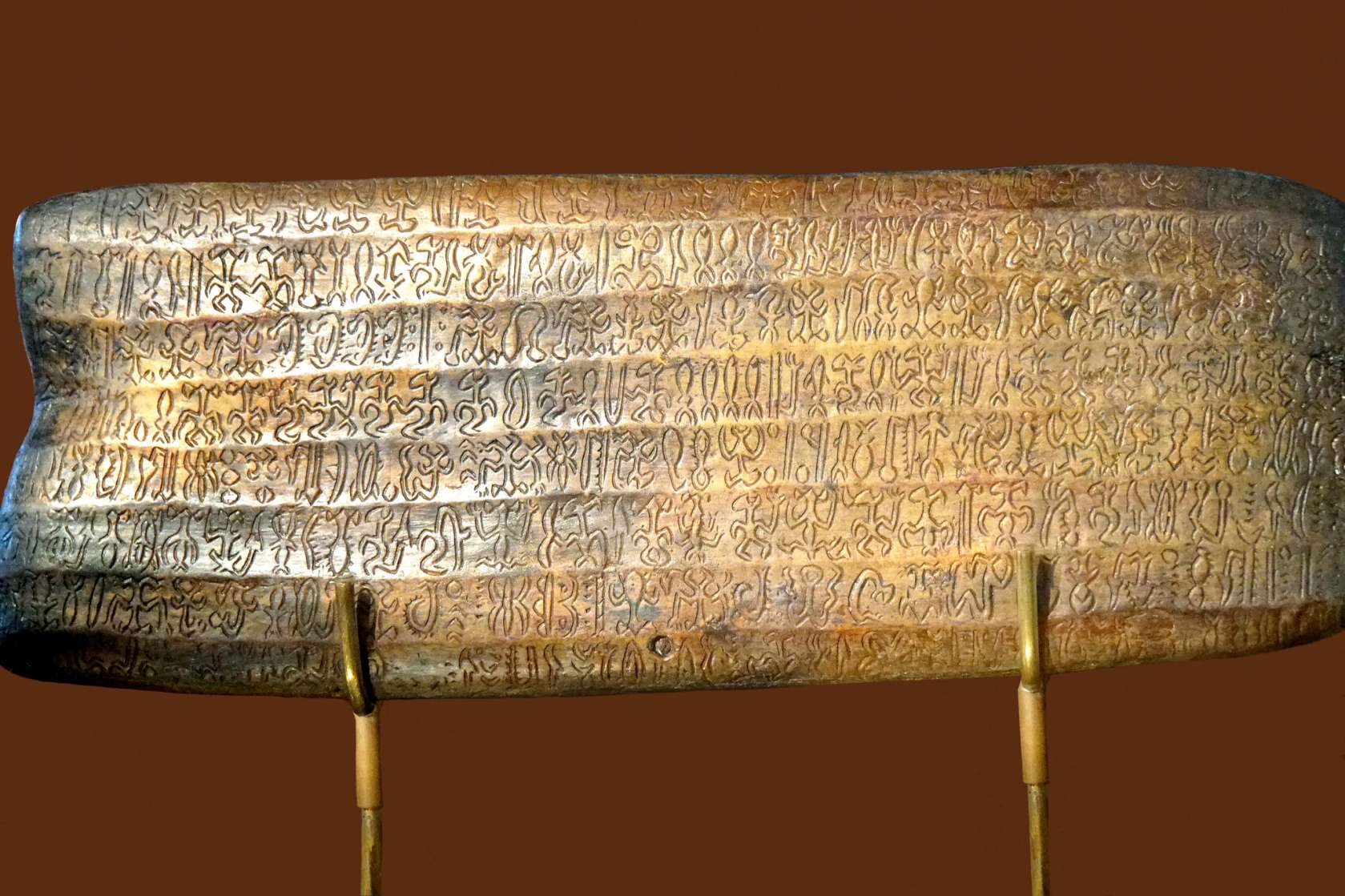

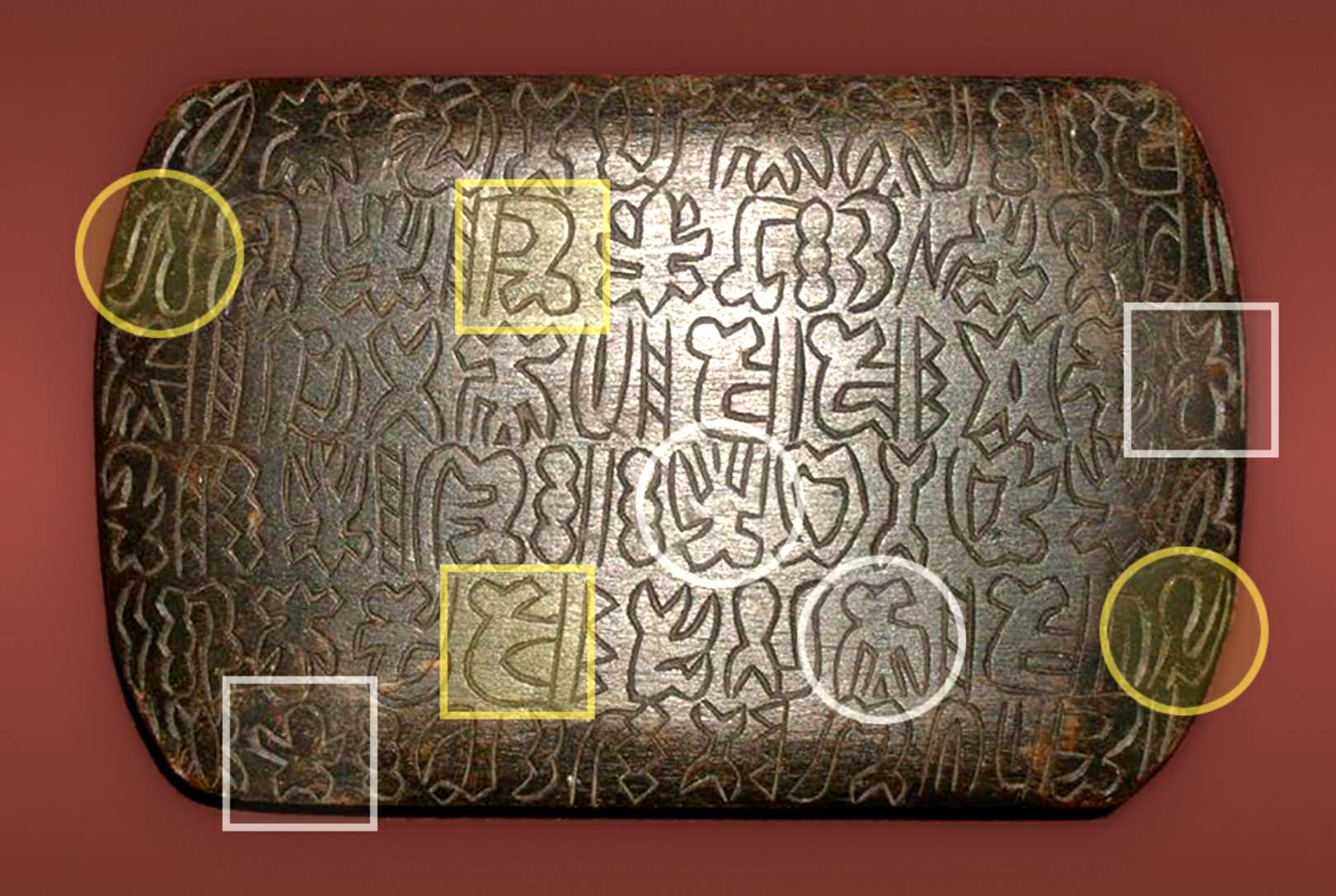

Rongorongo is a pictograph-based writing or Proto-writing system. It has been discovered etched into various oblong wooden tablets and other historical relics from the island. The art of writing was unknown on any surrounding islands, and the script’s sheer existence perplexed anthropologists.

So far, the most credible interpretation has been that the Easter Islanders were inspired by the writing they saw when the Spanish claimed the island in 1770. However, despite its recency, no linguist or archaeologist has been able to successfully decipher the language.

I le Rapa Nui language, which is the indigenous language of Easter Island, the term Rongorongo means “to recite, to declaim, to chant out.” When the oddly shaped wooden tablets were discovered, they had deteriorated, been burned, or had been severely damaged. A chieftain’s staff, a bird-man statuette, and two reimiro ornaments were also discovered with the glyphs.

Between the lines that travel across the tablets are inscribed the glyphs. Some tablets have been “fluted,” with the inscriptions being contained inside the channels generated by the fluting process. They are shaped like human beings, animals, vegetation, and geometric shapes in the Rongorongo pictograph. In every symbol that features a head, the head is orientated so that it is looking up and either facing forward or profiling to the right.

Each of the symbols has a height of around one centimeter. The lettering is laid out so that it is read bottom-to-top, left-to-right. Reverse boustrophedon is the technical term for this. In accordance with oral tradition, the engravings were created using obsidian flakes or small shark teeth as the primary tools.

Since only a few direct dating studies have been conducted on the tablets, it is impossible to determine their exact age. However, they are thought to have been created around the 13th Century, at the same time that forests were cleared. However, this is only theoretical, as the inhabitants of Easter Island may have felled a small number of trees for the explicit purpose of constructing the wooden tablets. One glyph, which resembles a palm tree, is believed to be the Easter Island palm, which was last recorded in the island’s pollen record in 1650, indicating that the script is at least that old.

The glyphs have proven to be challenging to decipher. Taking the supposition that Rongorongo is writing, there are three obstacles that make deciphering it difficult. The limited number of texts, the dearth of illustrations and other contexts with which to comprehend them, and the poor attestation of the Old Rapanui language, which is most likely the language reflected in the tablets, are all factors that have contributed to their obscurity.

Others feel that the Rongorongo is not actual writing, but rather proto-writing, meaning a collection of symbols that but do not include any linguistic content in the traditional sense.

E tusa ai ma le Atlas of Language database, “The Rongorongo was most likely employed as a memory aid or for ornamental purposes, rather than to record the Rapanui language spoken by the islanders.”

While it is still unclear exactly what the Rongorongo is intended to communicate, the discovery and examination of the tablets have proven to be a significant step forward in our understanding of the ancient civilizations of Easter Island in the past.

Because the figures are meticulously carved and perfectly aligned, it is clear that the ancient island culture had a message to send, whether it was a casual exhibition for decorative purposes or a method of transmitting messages and stories from generation to generation.

Although it is possible that understanding the codes will one day provide answers as to why the island civilization collapsed, for now, the tablets serve as an enigmatic reminder of times gone.