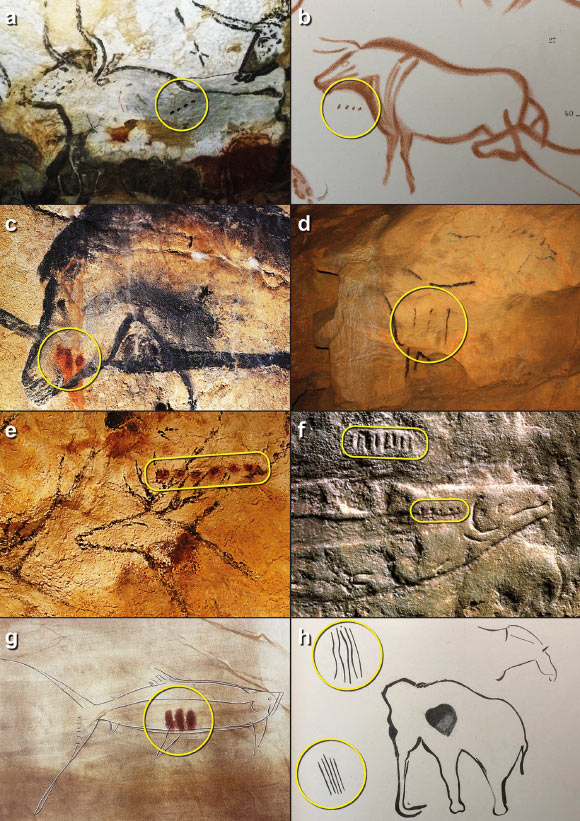

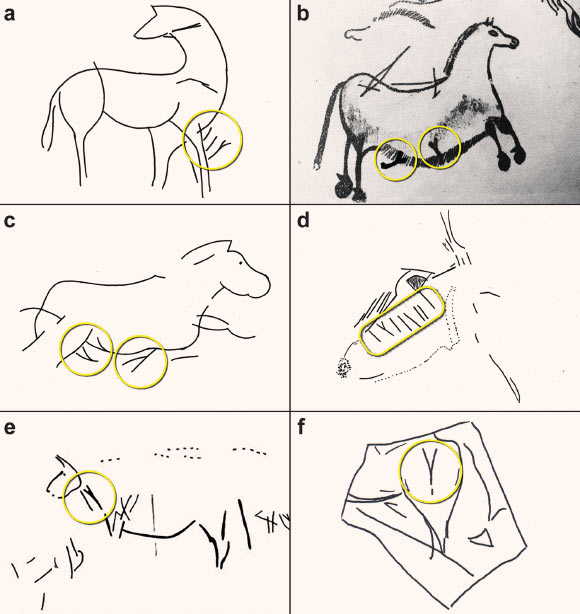

In more than 400 European caves including lascaux, Chauvet și Altamira, Upper Paleolithic humans drew, painted and engraved non-figurative signs from at least 42,000 years ago and figurative images — notably animals – from at least 37,000 years ago. Since their discovery 150 years ago, the purpose or meaning of these non-figurative signs has eluded researchers. New cercetare by independent researchers and their professional colleagues from University College London and the University of Durham suggests how three of the most frequently occurring signs — the line ‘|’, the dot ‘•’, and the ‘Y’ — functioned as units of communication. The authors demonstrate that when found in close association with images of animals the line ‘|’ and dot ‘•’ constitute numbers denoting months, and form constituent parts of a local phenological/meteorological calendar beginning in spring and recording time from this point in lunar months; they also demonstrate that the ‘Y’ sign, one of the most frequently occurring signs in Paleolithic non-figurative art, has the meaning ‘To Give Birth.’

Around 37,000 years ago humans transitioned from marking abstract images such as handprints, dots and rectangles on cave walls to drawing, painting and engraving figurative art.

These images, whether created on rock surfaces in the open air, in caves, or carved and engraved onto portable materials, were almost exclusively of animals, mainly herbivorous prey critical to survival in the Pleistocene Eurasian steppes.

In most cases it is easy to identify the species depicted, and often the characteristics they exhibit at particular times of year.

In Lascaux around 21,500 years ago, body shapes and pelage details were used to convey information about the sequence of rutting of several prey species on the cave’s walls.

Alongside these images, sets of abstract marks, particularly sequences of vertical lines and dots, ‘Y’ shapes and various other marks are common throughout the European Upper Paleolithic, occurring either alone or adjacent to and superimposed upon animal depictions, as has long been recognized.

In the new study, independent researcher Ben Bacon and his colleagues found that these marks record information numerically and reference a calendar, rather than recording speech.

The markings therefore cannot be called ‘writing’ in the same sense as pictographic and cuneiform systems of writing that emerged in Sumer from 3,400 BCE onwards.

The authors refer to the markings as a ‘proto-writing’ system, which pre-dates other token-based systems that emerged during the Near Eastern Neolithic period by at least 10,000 years.

“The meaning of the markings within these drawings has always intrigued me so I set about trying to decode them, using a similar approach that others took to understanding an early form of Greek text,” Bacon said.

“Using information and imagery of cave art available via the British Library and on the Internet, I amassed as much data as possible and began looking for repeating patterns.”

“As the study progressed, I reached out to friends and senior university academics, whose expertise were critical to proving my theory.”

The scientists used the birth cycles of equivalent animals today as a reference point to work out that the number of marks associated with Ice Age animals was a record, by lunar month, of when they were mating.

They worked out that a ‘Y’ sign used stood for ‘giving birth’ and found a correlation between the numbers of marks, the position of the ‘Y’ and the months in which modern animals mate and birth respectively.

“Lunar calendars are difficult because there are just under twelve and a half lunar months in a year, so they do not fit neatly into a year,” said University College London’s Professor Tony Freeth.

“As a result, our own modern calendar has all but lost any link to actual lunar months.”

“In the Antikythera Mechanism, they used a sophisticated 19-year mathematical calendar to resolve the incompatibility of the year and the lunar month — impossible for Paleolithic peoples.”

“Their calendar had to be much simpler. It also had to be a ‘meteorological calendar,’ tied to changes in temperature, not astronomical events such as the equinoxes.”

“With these principles in mind Ben and I slowly devised a calendar which helped to explain why the system that Ben had uncovered was so universal across wide geography and extraordinary time-scales.”

“The study shows that Ice Age hunter-gatherers were the first to use a systematic calendar and marks to record information about major ecological events within that calendar,” said Durham University’s Professor Paul Pettitt.

“In turn we’re able to show that these people, who left a legacy of spectacular art in the caves of Lascaux and Altamira, also left a record of early timekeeping that would eventually become commonplace among our species.”

“The implications are that Ice Age hunter-gatherers didn’t simply live in their present, but recorded memories of the time when past events had occurred and used these to anticipate when similar events would occur in the future, an ability that memory researchers call mental time-travel,” said Durham University’s Professor Robert Kentridge.

The researchers hope that deciphering more aspects of the proto-writing system will allow them to develop an understanding of which of information early humans valued.

“As we probe deeper into their world, what we are discovering is that these ancient ancestors are a lot more like us than we had previously thought,” Bacon said. “These people, separated from us by many millennia, are suddenly a lot closer.”

Echipa paper was published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.