The Paleolithic butcher expertly wielded a sharp stone blade to slice off the meatiest chunk of the lower leg. After they had finished, they were able to enjoy the fruits of their labor with a hearty meal derived from the remains of another early human.

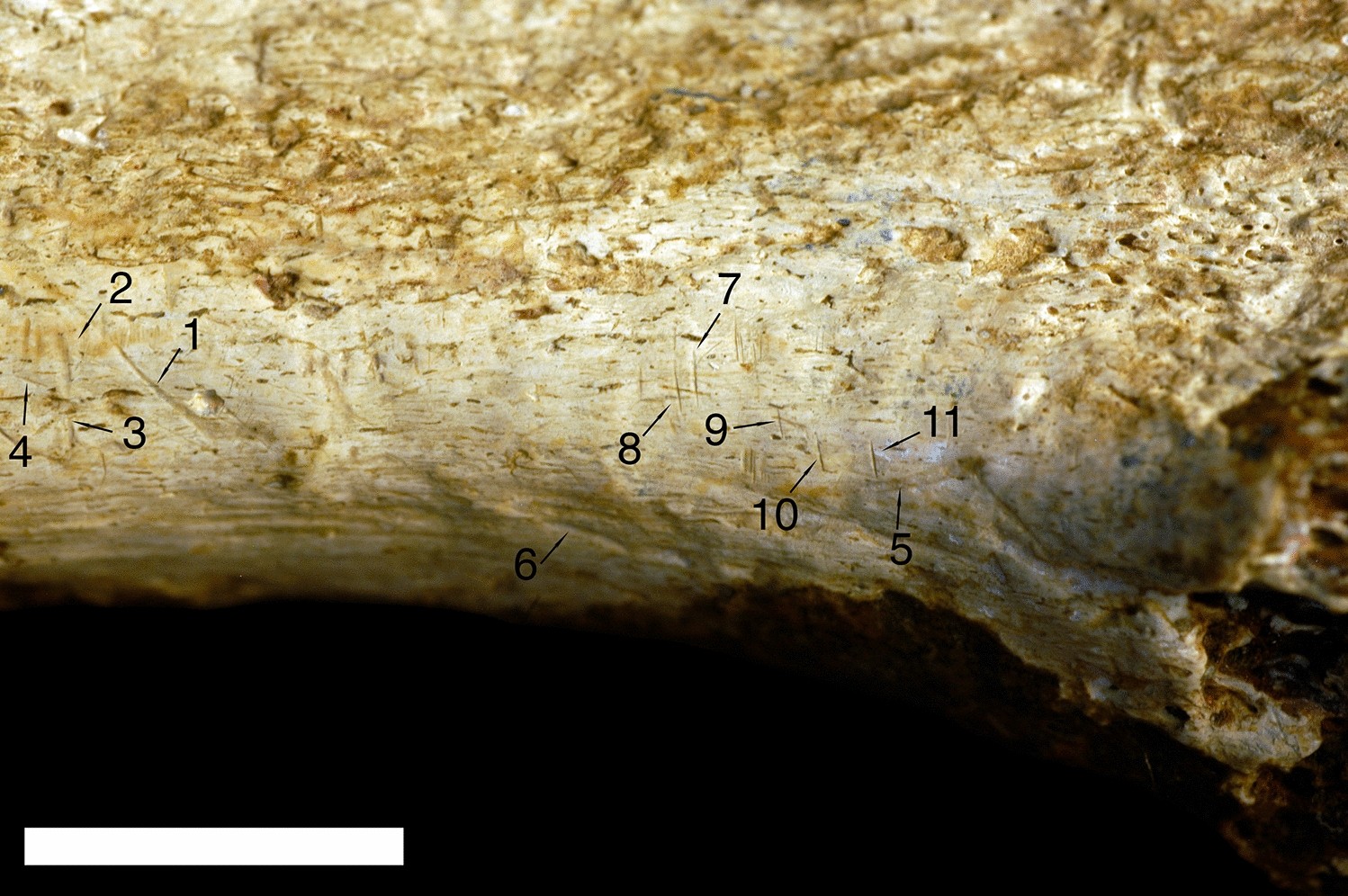

Previously unnoticed cut marks located on a 1.45-million-year-old shin bone that were recently discovered in a Kenyan museum may be the earliest known proof of how ancient human relatives used to butcher and consume one another. Nine distinct cuts, all going in the same direction, were observed on the area where the calf muscle attaches to the bone, indicative of a stone tool technique typically used to remove meat. Additionally, two bite marks were found on the bone, suggesting that a big cat also had a bite at some point.

Though only the shin bone has been found, it is not possible to identify which particular type of Homo sapiens relative was the target of the meal. Additionally, it is uncertain whether the same species or a different relation consumed the calf muscle. It is possible that the discovery marks the earliest known demonstration of cannibalism if the same species was involved. Even if this is not the case, the scene still displays one ancestor dining on another, and not in a hospitable way.

Briana Pobiner of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, who specializes in the development of human diet, states that, “We just know that some tool-wielding hominin came and cut meat off of that bone.”

A study on the find, of which Pobiner is a co-author, was released publicly on Monday 26th June in the journal Scientific Reports.

In 1970, the renowned anthropologist Mary Leakey discovered the fossil among many others in Kenya’s Turkana region. Fast-forward to 2017, when Pobiner examining collections at the Nairobi National Museum. She was hoping to find bite marks on ancient human relatives’ bones in order to gain insight into which animals had preyed on them, never expecting to find another human species among those predators — or at least among the scavengers.

“I’ve seen tool marks on many animal fossils from this area and time period, so I thought, Wow, I definitely know what this is,” Pobiner recalls. “But I also thought — Surprise! This is definitely not what I thought I would find.”

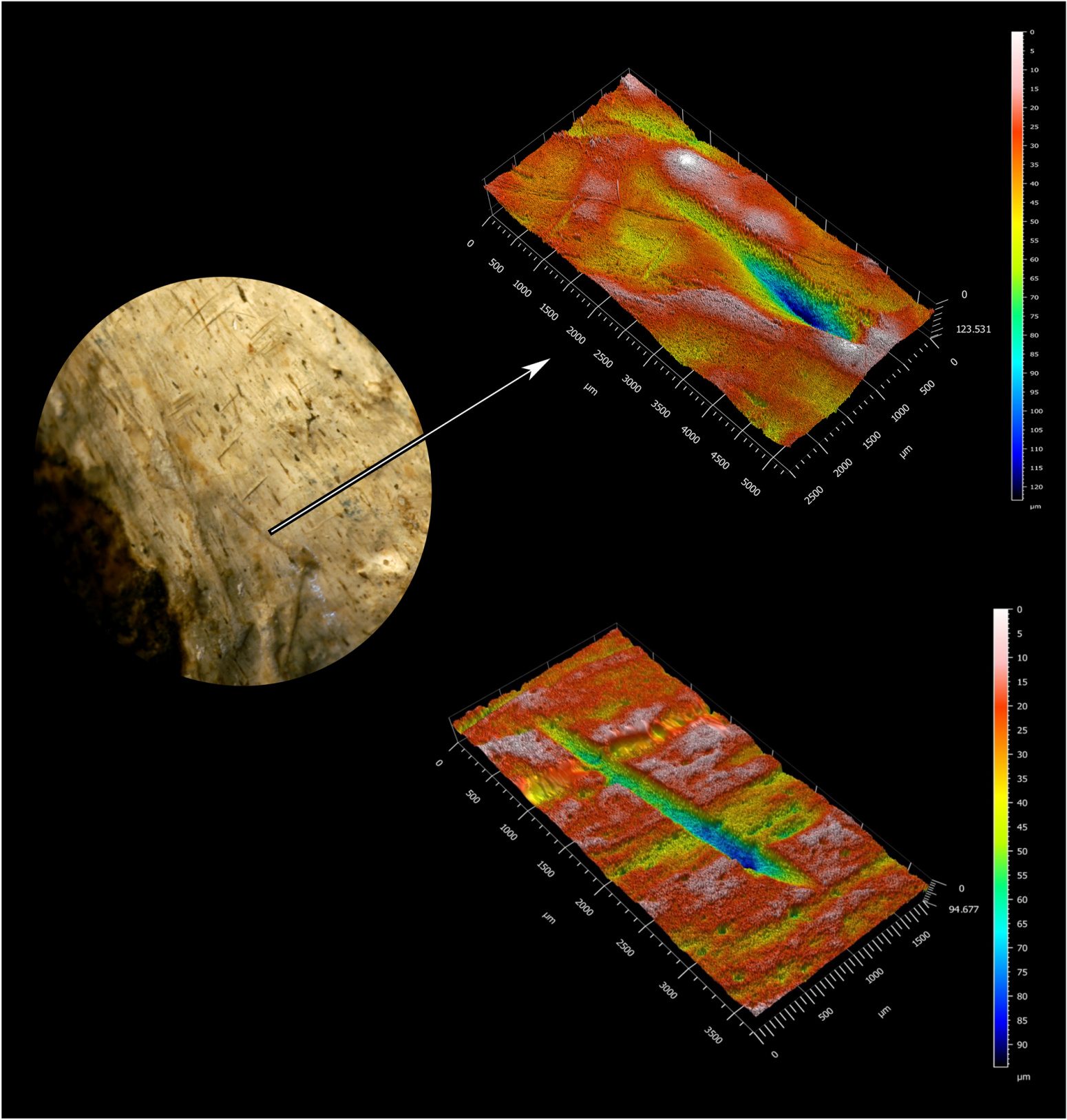

Pobiner utilized a stringent examination to determine the cut marks. She molded the marks with the same materials a dentist would use to create teeth molds and sent them to co-author Michael Pante, a paleoanthropologist at Colorado State University. She shared no background information on where they were from or what she suspected they were.

Michael Pante and Trevor Keevil, a researcher from Purdue University’s Laboratory for Computational-Anthropology and Anthroinformatics, collaborated to analyze a database of almost 900 different tooth, butchery and bone markings. These impressions were fresh, comprising bite marks from carnivorous animals and cuts from tools. Each imprint was confirmed to have originated from a known origin, thus allowing them to distinguish unrecognized examples through comparison.

To further investigate the bone molds, Pante created 3D scans and matched the results with the database. He found that 9 of the 11 marks were created with stone tools, while the remaining two were likely made by a big cat. “The work that Michael Pante and Trevor Keevil did with all the modern marks is hugely important,” Pobiner says. “That’s how we can use the present to understand the past.”

The details of this intriguing discovery are yet to be comprehended, including the identities of the two individuals involved — the victim and the butcher.

Since the shin bone’s discovery, there has been debate among researchers in regards to what hominin it belonged to, whether it was Paranthropus boisei or Homo erectus. No agreement has been reached yet. Scientists are also uncertain what the butcher’s motive was.

Palmira Saladié Ballesté, an archaeologist from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution, commented that it is hard to draw any conclusions about the situation based on a single bone that has signs of butchery. “However, in any case, it would involve the defleshing of a technologically advanced hominin by another technologically advanced one,” she says. “From this perspective, it can be considered cannibalism.”

And the human butcher wasn’t the only individual who attempted to make a meal of this particular leg bone. The two bite marks, apparently those of a big cat, are closest to matching the lion among living species. However, it could have been the work of saber-toothed cats or some other extinct species of cats, since they are no longer here to be included in the bite database.

This unknown cat may have killed the unfortunate victim and chewed on its leg before being driven off by humans who later took charge of the body. Or hominins could have killed and butchered the unfortunate victim before big cats got to the scraps.

It is also possible that no violence was the cause of death. Perhaps an individual simply passed away and then scavengers of several species took advantage of a free meal. According to Pobiner, “Lions do a lot of scavenging, and there’s no reason to think that any big predator on the ancient African savanna wouldn’t have also scavenged — including early humans.”

Although more than 1,300 species, including some primates, are cannibalistic, the practice is considered taboo across most modern human societies. Researchers can’t be sure how our prehistoric relatives felt about it, or the various reasons that they ate their own kind in different times and places. But, perhaps surprisingly, the evidence shows that it wasn’t all that uncommon.

A South African skull that may have existed between 1.5 and 2.6 million years ago has been put forward as a potential example of a human ancestor that was cannibalized by its peers. But Pobiner notes that the skull’s age is uncertain, as are interpretations of the cut marks found below its right cheek bone. Scholars have disagreed whether these marks were made by stone tools, and, if so, if they would have been related to cannibalism—the relative lack of edible flesh in the skull complicates this hypothesis.

From the early stages of Homo sapiens development, there have been examples of cannibalism. Starting about a half million years ago, evidence of cannibalism has been frequently observed in fossils of Neanderthals and H. sapiens. “The interpretation with Neanderthals, particularly, is that they lived in marginal environments where they were food-stressed,” Pobiner notes. “We don’t really see evidence of aggression or rituals. We see Neanderthals being butchered and dumped in pits with other animals. So we think they were probably just eating people because they were food.”

Silvia Bello, an anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, thinks cannibalism might have been more common than expected. Many human remains aren’t preserved at all, and butchery marks aren’t always visible, she notes. “Some tissue may be eaten without leaving marks on bones, or bodies could have been completely consumed, as is the case of the Wari in South America, therefore leaving no evidence.”

Few would suggest that humans frequently hunted each other down for food. Even if they had no qualms about killing and eating each other, easier, less intelligent prey would have likely formed the basis of their diet. Besides, when University of Brighton archaeologist James Cole broke down the nutritional value of human meat, he found our bodies’ caloric values so low that other Paleolithic prey would have been far more desirable.

Instead, cannibalistic meals may have been dietary supplements. Our ancestors simply took advantage of the deceased as easy pickings—at least during earlier stages of our evolution. Other, younger sites from a wide range of time do show evidence of what appears to be ritual or cultural cannibalism, both within groups and representing aggression between groups.

At Gran Dolina, Spain, 11 young Homo antecessor individuals were butchered, and their brains apparently consumed, over a period of time about 800,000 years ago. Some experts, drawing parallels with chimpanzees that protect their territory by killing and eating the young of neighboring groups, interpret those Spanish remains as the result of similar conflicts. At England’s Gough’s cave, human bones that had been defleshed and chewed some 15,000 years ago also bear ritualistic markings that suggest cannibalism there may have begun to take on ceremonial or symbolic aspects.

Bello thinks that once Neanderthals and modern humans began to develop funerary rituals 100,000 years ago, cannibalism may have acquired ritualistic components, becoming more than a meal. “The reasons why this shift [occurred] may be the same as the reasons why humans started to bury and ritualize bodies,” she notes.

Though cannibalism exists in modern times, most humans find it a distasteful prospect that they’d rather not dwell on. But for those delving into the eat-or-be-eaten environments in which our ancestors survived, the topic keeps coming up, and finds like Pobiner’s push it back further toward our evolutionary origins.

“It’s interesting to think,” she notes, “about how long our ancestors and relatives have been seeing other people as potential food.”

The study originally published in the journal Scientific Reports. 26 June 2023.