A new and improved DNA analysis of the famous ‘Iceman’ mummy suggests this ancient individual is not who we thought he was. The 5,300-year-old mummy, nicknamed Ötzi (which rhymes with “tootsie”), is the oldest human body ever found intact.

He has fascinated the world since his body was first unearthed in Italy’s Ötztal Alps in 1991. But the way most people imagine this 46-year-old man isn’t necessarily accurate.

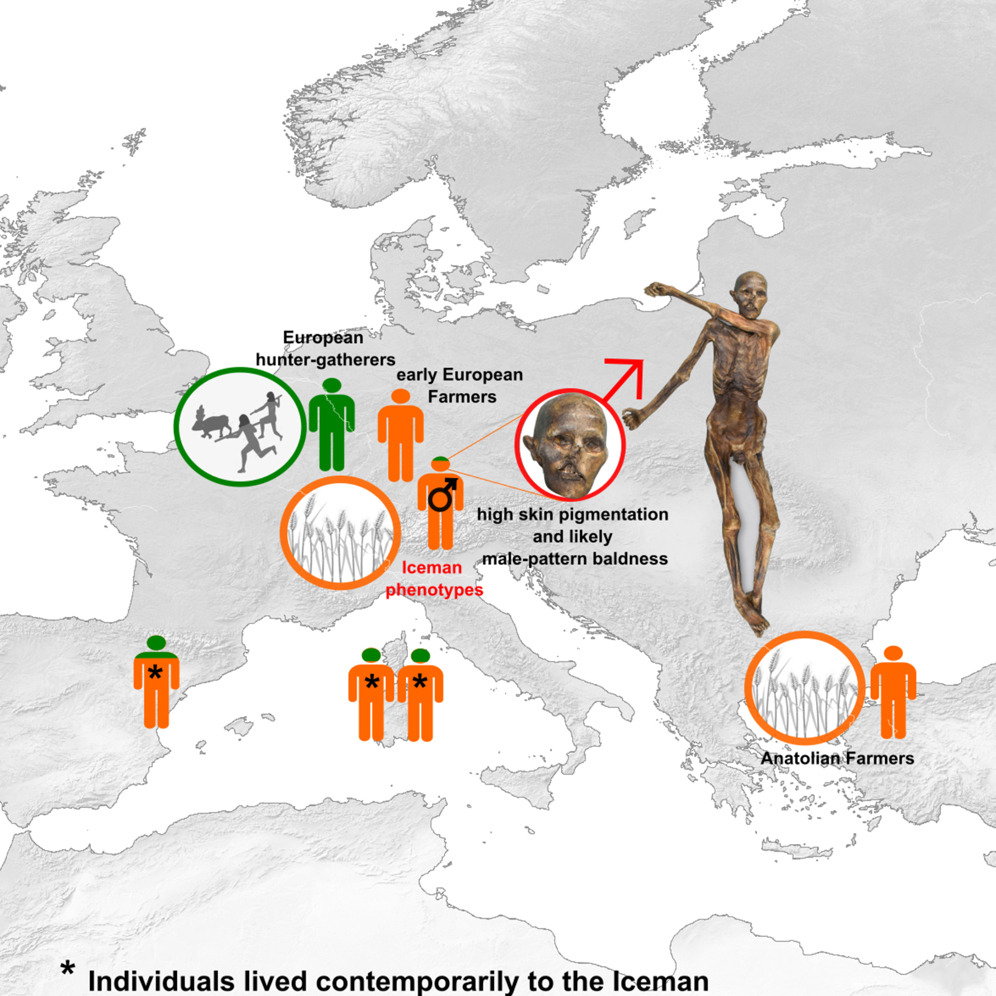

According to a study, led by researchers at Germany’s Max Planck Institute, Ötzi may not be a hairy, caucasian hunter-gatherer, as previous reconstructions suggested, but a farmer with relatively dark skin and a balding head.

“The genome analysis revealed phenotypic traits such as high skin pigmentation, dark eye color, and male pattern baldness that are in stark contrast to the previous reconstructions that show a light skinned, light eyed, and quite hairy male,” says evolutionary anthropologist Johannes Krause from the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

Scientists might know what Ötzi last ate and what his voice might have sounded like, but what he looked like is another matter.

The first genome study on Ötzi took place back in 2012 and found evidence that this man was closely related to present-day Sardinians. As such, it was assumed he was descended from populations of eastern hunter-gatherers and caucasian hunter-gatherers who merged in the fifth millennium.

But the new findings found no detectable ancestry of this kind. Instead, researchers uncovered “unusually high” Anatolian farmer ancestry in Ötzi’s genome, higher than almost any other known population in Europe at that time.

The findings suggest Ötzi was closely related to a lineage of Neolithic farmers in Anatolia, where the country of Türkiye now sits. They later migrated to Italy but remained relatively isolated in the Alps, keeping to themselves.

Ötzi’s ancestors may have started mixing with hunter-gatherers elsewhere in Europe just a few dozen generations before his birth – a relatively short time in terms of a population’s evolution.

In Ötzi’s genome, researchers found evidence of an agricultural diet and skin pigmentation that is darker than that typically found across present-day European populations.

They also found risk alleles associated with male-pattern baldness. Whatever hair the hunter once had was probably black.

The findings match the appearance of the mummy itself, explains Krause, which is dark and has no hair. But previous studies assumed that this appearance was the result of being frozen for millennia, not an accurate representation of Ötzi’s looks in life.

The authors of the new analysis acknowledge that “a single individual has… limited resolution in representing the population history of his time and region”, but their results do match other ancient humans found in Italy.

One body found near the southern Alps, for instance, also shows high Anatolian-farmer-related ancestry in recent genome studies.

“Future studies with a denser sampling from the southern Alps will be needed to replicate our findings and show if the Iceman was an outlier or a representative of his population,” the researchers conclude.

The study originally published in the journal Cell Genomics. August 16, 2023.