An international research team at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany has made a noteworthy development – for the first time it has succeeded in isolating human DNA from an object from the oldest Stone Age period.

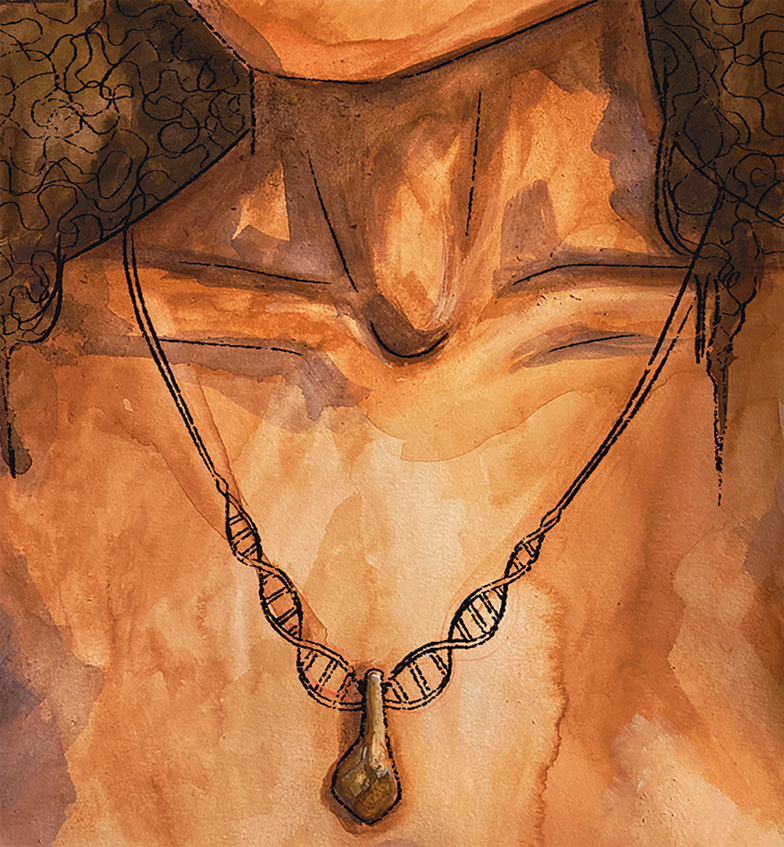

The researchers discovered the DNA in a tooth that was already 20,000 years old and hanging from a necklace. This new technique will allow us to learn much more about our earliest relatives.

A deer tooth has been found in the famous Denisova cave in the Altaige Mountains in southern Siberia, which has been home to Homo sapiens and the extinct Denisova for thousands of years.

The researchers created a genetic profile of the pendant’s carrier from the DNA samples. They determined that it was a woman related to the northern Eurasian people who resided mainly further east in Siberia.

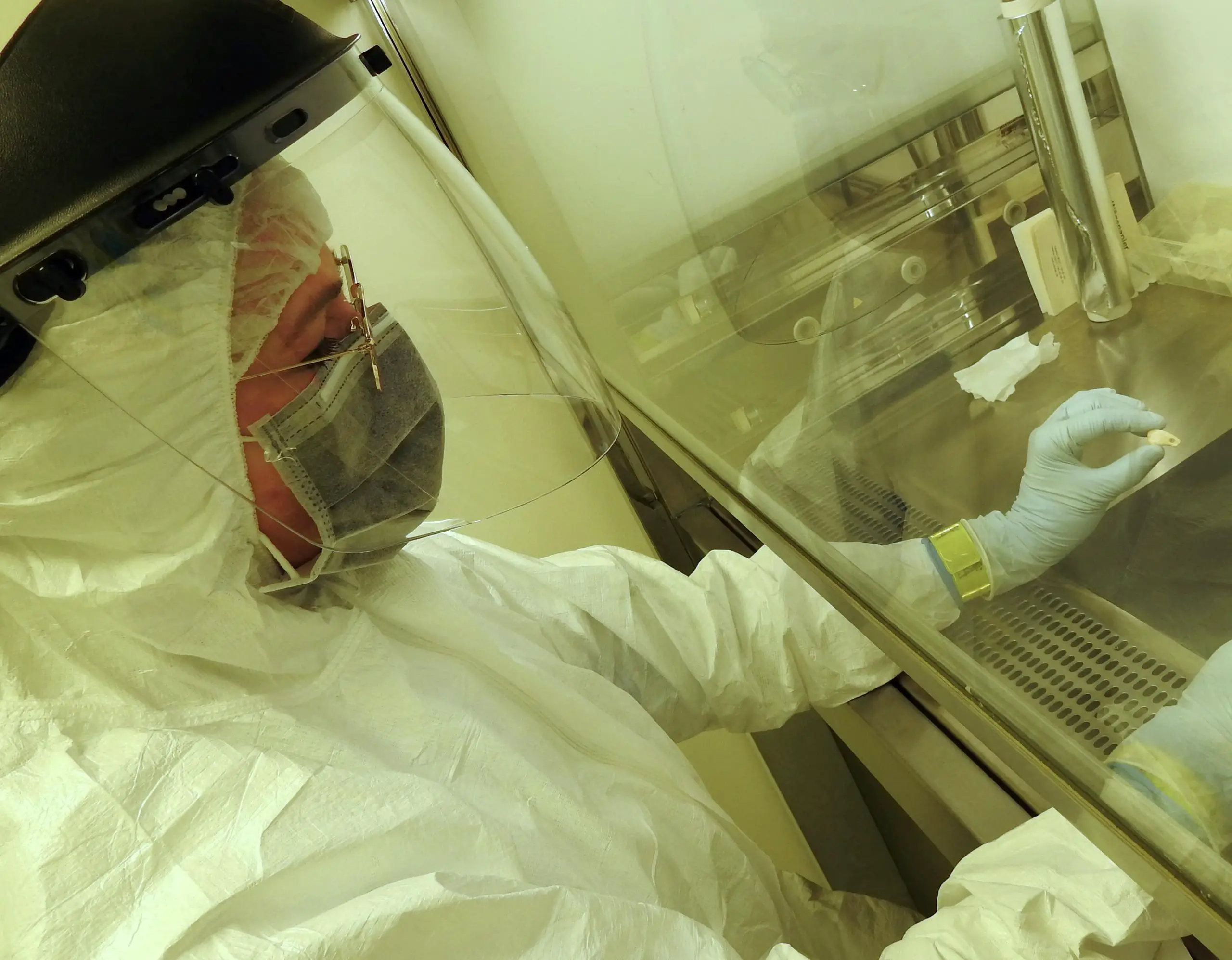

The essential step for applying the new DNA method is thorough washing

Scientists have developed a way to extract DNA from skin cells, perspiration or other body fluids embedded in pore material. So, if someone had touched bones or teeth 20,000 years ago, for example, there is a possibility that researchers can now isolate the DNA.

According to Elena Essel, the lead researcher, the amount of human DNA we can recover is almost as impressive as if we had a human tooth.

This technique is so impressive because it is completely non-invasive and non-destructive.

After experimenting with different chemicals on bones and teeth, the German team found that it was enough to thoroughly clean the bones in a solution of phosphate and warm water – which made it easy to identify the DNA. Thorough washing also has the advantage of removing pores and small holes, which can contain DNA residues.

According to Essel, it is possible to wash antique objects in a type of washing machine designed specifically for this purpose. By washing them at temperatures of up to 90 degrees, DNA molecules are removed from the rinse water without compromising the original object.

A new chapter is opened for genetic research

According to the research article published in the journal Nature, anthropologists from the Max Planck Institute argue that their recently developed DNA procedure will be the starting point of a new phase of research into prehistoric genetics.

Archaeologists and anthropologists used to have almost no chance of discovering who owned tools, jewelry and personal objects made from bones and teeth. But now they can gain important insights from them.

By using this method, you ensure that objects and people are more connected, creating a more detailed and complex picture of people, their societies and cultures from thousands of years ago.