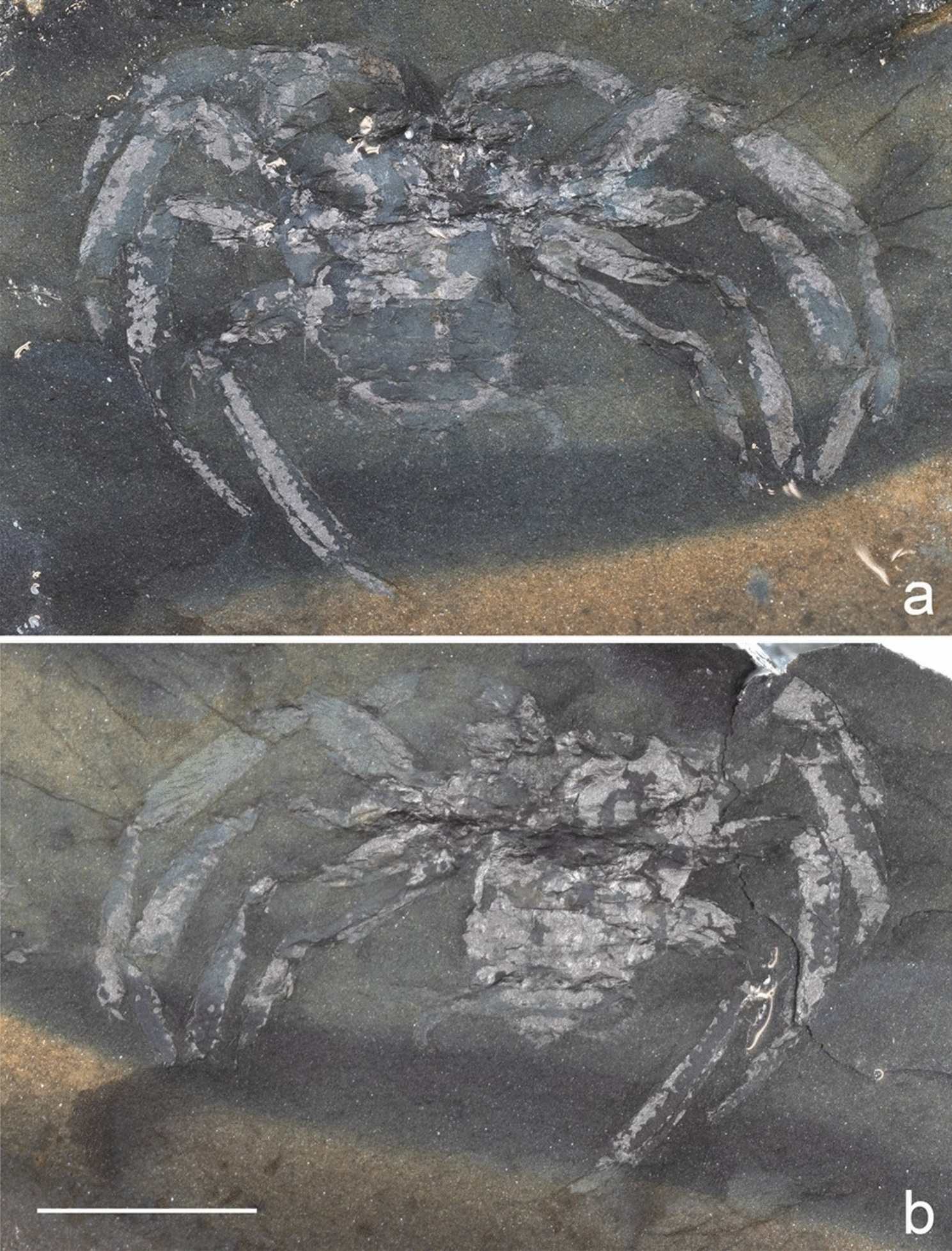

A few years ago, an ancient spider fossil of an unknown species was found in Piesberg near Osnabrück in Lower Saxony, Germany. The fossil is from the Late Carboniferous (Moscovian) period. The fossil originates from a layer of rock that is estimated to be between 310 and 315 million years old. It represents the earliest known spider from the Palaeozoic era discovered in Germany.

Additionally, it has been classified as a new species and given the name Arthrolycosa wolterbeeki, honoring the discoverer – Dr. Tim Wolterbeek, a geosciences researcher at Universiteit Utrecht. Following the finding, Wolterbeek gave the specimen to fossil arachnid expert Jason Dunlop of the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin for further examination.

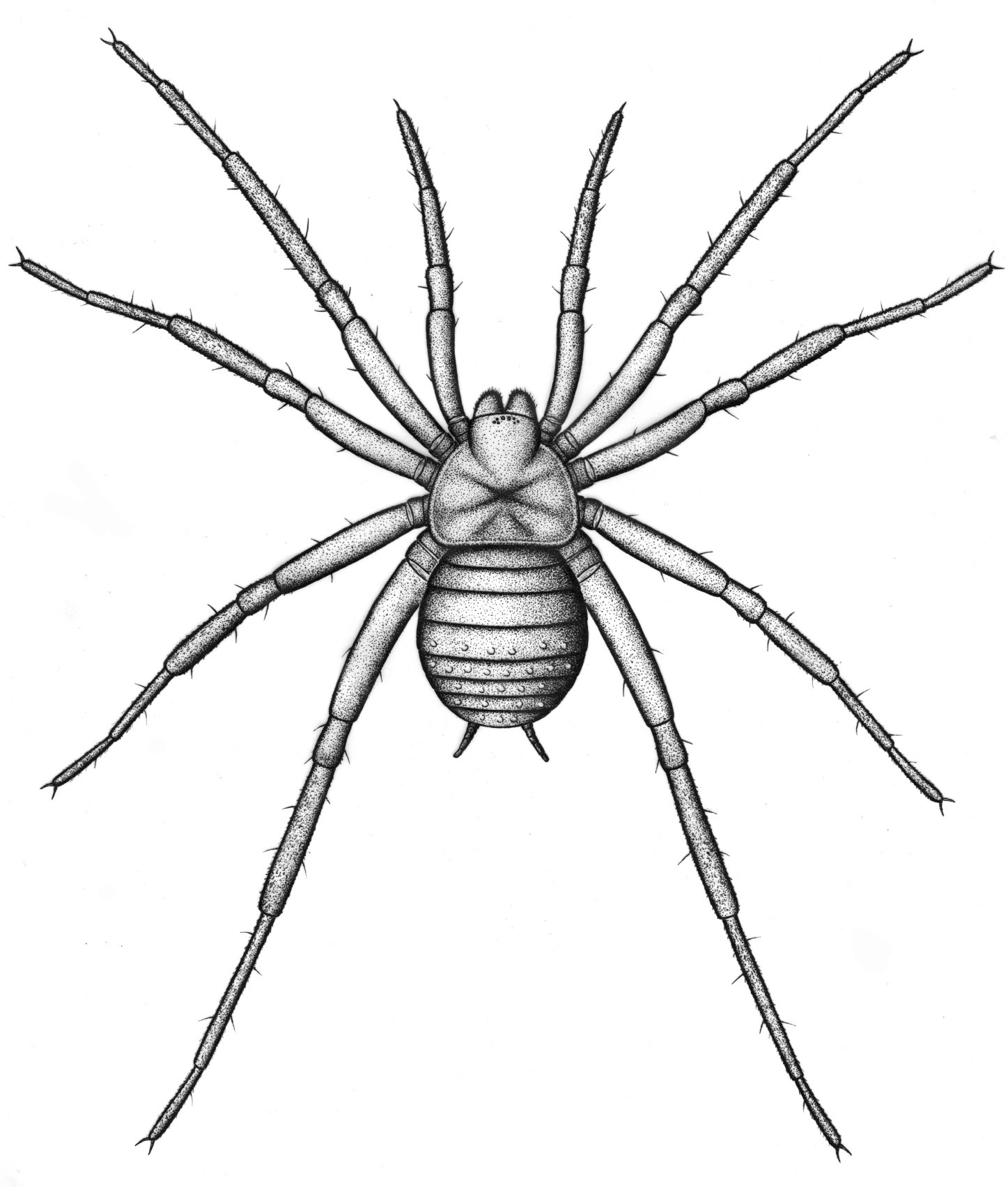

A. wolterbeeki, the first recognized “true spider” from Germany’s Palaeozoic era, belongs to the Araneae order. This distinguishes it from previous spider-like arachnids such as the Trigonotarbids, which had a bulkier lower body. Apart from its long legs, the fossil also exhibits preserved spinnerets, a key trait unique to true spiders.

Despite its incredible age, the fossil spider is remarkably preserved as a nearly complete specimen. It has managed to survive in the fossil record and has been identified as one of only twelve Carboniferous species that can be definitively classified as Araneae.

Although we currently have twelve known species, the number of spider species during the Carboniferous period is pretty low compared to related arachnids like Phalangiotarbids and previously mentioned Trigonotarbids. These closely-related arachnids have twice and four times the number of species, respectively.

One possible explanation for this could be the similarities between A. wolterbeeki and the current mesothele spiders. If they were ecologically similar and shared the same burrow-dwelling lifestyle, it’s plausible that they had limited chances of becoming fossils because they rarely encountered water bodies necessary for preservation.

It is highly improbable for female spiders to be preserved in the fossil record because they tend to be mostly sedentary, a fact we observe in present-day spiders. In contrast, once male spiders reach maturity, they actively explore to find a partner. However, our current discoveries indicate that even their chances of being fossilized are not any higher.

According to Jason Dunlop, “It is interesting to consider why neither the present specimen, nor any of the other Carboniferous spiders, preserve a male palpal organ as we might expect wandering males to be preferentially preserved.”

Regardless, the Piesberg-fossil is now considered a significant holotype of the Araneae, and serves as a delightful reminder that a scientist’s expertise extends beyond their specific field of study.

The study originally published in the journal PalZ, published online 16 July 2023.