Understanding the thought processes of Paleolithic man is not an easy feat. The veil of time is a perpetual mystery, a cloud that envelops human history and casts a shadow of secrets, riddles, and perplexing archaeological finds. But what we have so far is far from primitive.

There is so much more to the Paleolithic man than we can imagine at first. He had a complex and natural view of the world and a perfect relationship with nature, which was a true and right bond. The Lascaux Cave, a masterpiece of Paleolithic cave art and a significant image of the world that existed around 17 millennia ago, is ideal proof of early man’s heightened awareness of the natural environment.

Join us as we follow in the footsteps of our hunter-gatherer forefathers, through the cryptic and wild world of the Upper Paleolithic in an attempt to comprehend the enigmatic world of the man that was.

The accidental discovery of the Lascaux Cave

The Lascaux Cave is located in southern France, near the commune of Montignac in the Dordogne region. This amazing cave was found by accident in 1940. And the one who made the discovery was… a dog!

On September 12, 1940, while out for a stroll with its owner, an 18-year-old boy called Marcel Ravidat, a dog named Robot fell into a hole. Marcel and three of his adolescent pals decided to descend into the hole in the hopes of rescuing the dog, only to realize that it was a 50-foot (15-meter) shaft. Once inside, the youngsters realized they had stumbled onto something absolutely unusual.

The cave system’s walls were decorated with bright and realistic images of various animals. The boys returned around 10 days later, but this time with someone more competent. They invited Abbe Henri Breuil, a Catholic priest, and archaeologist, as well as Mr. Cheynier, Denis Peyrony, and Jean Bouyssonie, his colleagues and specialists.

They toured the cave together, and Breuil made several precise and significant drawings of the cave and the murals on the walls. Unfortunately, the Lascaux Cave was not exposed to the public until eight years later, in 1948. And it was this that sealed its doom in part.

It caused a sensation and attracted a large number of people – almost 1,200 every day. The government and scientists failed to anticipate the ramifications for the cave art. The combined breaths of so many people within the cave each day, as well as the carbon dioxide, humidity, and heat they created, took their toll on the paintings, and many of them had been damaged by 1955.

Improper ventilation increased humidity, causing lichen and fungus to grow throughout the cave. The cave was eventually closed in 1963, and enormous efforts were undertaken to restore the art to its pristine form.

The various works of art that cover the walls of Lascaux Cave appear to be the work of multiple generations of people. This cave was clearly significant, either as a ceremonial or holy location or as a place of living. In any case, it is apparent that it was in use for many years, if not decades. The painting was created around 17,000 years ago, in the early Magdalenian civilizations of the Upper Paleolithic.

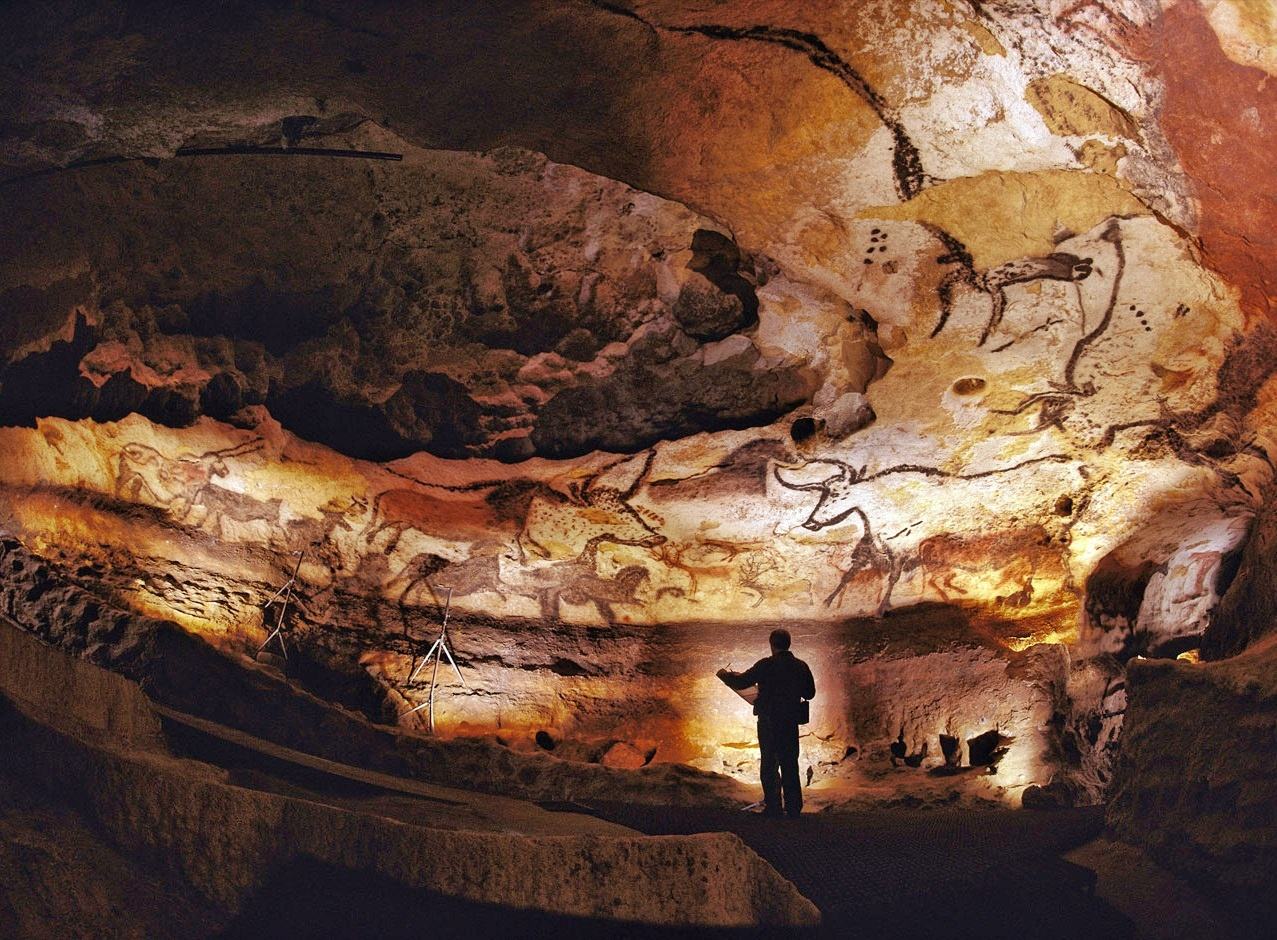

The Hall of Bulls

The most prominent and extraordinary section of the cave is the so-called Hall of Bulls. Seeing the art that is painted on these white calcite walls can truly be a breathtaking experience, providing a deeper and more meaningful bond with the world of our ancestors, with the mythical, primordial lives of the Paleolithic.

The main painted wall is 62 feet (19 meters) long, and it measures 18 feet (5.5 meters) at the entrance to 25 feet (7.5 meters) at its widest point. The high vaulted ceiling dwarfs the observer. The animals painted are all on a very large, impressive scale, some reaching 16.4 feet (5 meters) in length.

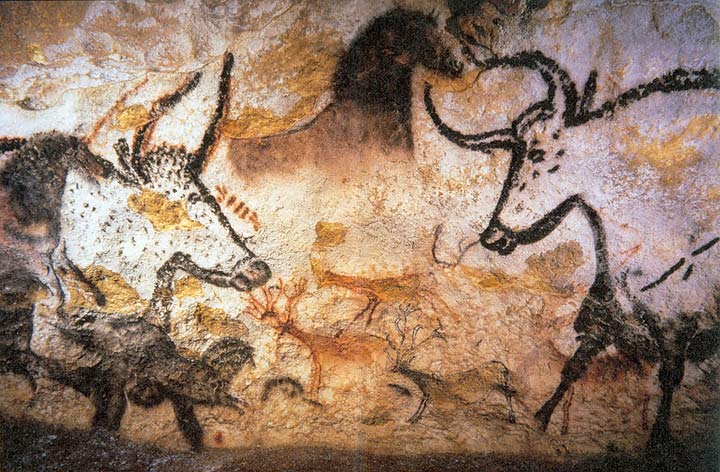

The largest image is that of an aurochs, a type of extinct wild cattle – thus the name the Hall of Bulls. There are two rows of aurochs painted, facing each other, with stunning accuracy in their form. There are two on one side and three on the opposite side.

Around the two aurochs are painted 10 wild horses and a mysterious creature with two vertical lines on its head, which seems to be a misrepresented aurochs. Beneath the largest aurochs are six smaller deer, painted in red and ochre, as well as the solitary bear – the only one in the entire cave.

Many of the paintings in the hall seem elongated and distorted because many of them were painted to be observed from one particular position in the cave which gives the undistorted view. The Hall of Bulls and the magnificent display of art in it has been cited as one of the great achievements of mankind.

The Axial gallery

The next gallery is the Axial one. It too is adorned with a host of animals, painted in red, yellow, and black. The majority of the shapes are those of wild horses, with the central and most detailed figure being that of a female aurochs, painted in black and shaded with red. A horse and the black aurochs are painted as falling – this reflects a common hunting method of the Paleolithic man, in which animals were driven to jump off of cliffs to their death.

High above is an aurochs head. All the art in the Axial gallery required scaffolding, or some other form of aid in order to paint the high ceiling. Besides the horses and aurochs, there is also a representation of an ibex, as well as several megaceros deer. Many of the animals were painted with stunning accuracy and the use of three-dimensional aspects.

There are also odd symbols, including dots and connected rectangles. The latter could represent some sort of a trap that was used in hunting these animals. The black aurochs are around 17 feet (5 meters) in size.

The passageway and the Apse

The part that connects the Hall of Bulls with those galleries called the Nave and the Apse is called the Passageway. But even though it is just that – a passageway – it holds a great concentration of art, giving it as much significance as a proper gallery. Sadly, due to the air circulation, the art has quite deteriorated.

It consists of 380 figures, including 240 complete or partial depictions of animals like horses, deer, aurochs, bison, and ibex, as well as 80 signs, and 60 deteriorated and indeterminate images. It also contains engravings on the rock, notably those of numerous horses.

The next gallery is the Apse, which has a vaulted spherical ceiling that reminds one of an apse in a Romanesque Basilica, thus the name. The ceiling at its highest is around 9 feet (2.7 meters) in height, and around 15 feet (4.6 meters) in diameter. Note that in the Paleolithic period, when the engravings were made, the ceiling was much higher, and the art could only have been made with the use of scaffolding.

Judging from the round, almost ceremonial shape of this hall, as well as an incredible number of engraved drawings and the ceremonial artifacts found there, it is suggested that the Apse was the core of Lascaux, a center of the whole system. It is noticeably less colorful than all the other art in the cave, mostly because all the art is in the form of petroglyphs, and engravings on the walls.

It contains over 1,000 figures displayed – 500 animal depictions and 600 symbols and markings. Many of the animals are deer and the only reindeer depiction in the entire cave. Some of the unique engravings in the Apse are the 6-foot (2-meter) tall Major Stag, the largest of the Lascaux petroglyphs, the Musk Ox panel, the Stag with the Thirteen Arrows, as well as the enigmatic carving called the Large Sorcerer – which still remains largely an enigma.

The mystery that is the shaft

One of the more mysterious portions of Lascaux is The Well or the Shaft. It has a 19.7 foot (6 meters) altitude difference from the Apse and can only be reached by descending the shaft via a ladder. This secluded and hidden part of the cave contains just three paintings, all done in the simple black pigment of manganese dioxide, but so mysterious and captivating that they are by far some of the most significant works of Prehistoric cave art.

The main image is that of a bison. It seems to be in an attacking position, and in front of him, seemingly struck, is a man with an erect penis and the head of a bird. Beside him is a dropped spear and a bird on a pole. The bison is seemingly depicted as being disemboweled or having a large and prominent vulva. The whole image is highly symbolic, and possibly depicts an important part of the belief of ancient Lascaux dwellers.

Besides this scene, is a masterly depiction of a wooly rhinoceros, besides whom there are six dots, in two parallel rows. The rhino seems much older than the bison and the other pieces of art, further attesting that Lascaux was the work of many generations.

The last image in the Shaft is a crude depiction of a horse. One amazing find that was discovered in the sediments of the floor, just below the image of the bison and the rhino, is a red sandstone oil lamp – belonging to the Paleolithic and the time of the paintings. It was used to hold deer fat, which provided light for the painting.

It looks like a large spoon which made it easy to hold while painting. Interestingly, upon discovery, it was found that the receptacle still contained remains of burnt substances. Tests determined that these were the remnants of a juniper wick that lit the lamp.

The Nave is the next gallery and it too displays stunning works of art. One of the most popular of the Lascaux art pieces is the depiction of five swimming stags. On the opposite wall are panels that display seven ibex, the so-called Great Black Cow, and the two opposing bison.

The latter painting, known as the Crossed Bison, is a stunning work of art, showing a keen eye that masterfully presented perspective and three dimensions. Such an application of perspective was not seen in art again until the 15th century.

One of the deepest galleries in Lascaux is the enigmatic Chamber of Felines (or Feline Diverticulum). It is roughly 82 feet (25 meters) long and quite difficult to reach. There are more than 80 engravings there, most of which are horses (29 of them), nine bison depictions, several ibexes, three stags, and six feline forms. The very important engraving in the Chamber of Felines is that of a horse – which is represented from the front as if looking at the viewer.

This display of perspective is unparalleled for the prehistoric cave paintings and shows the great skill of the artist. Interestingly, at the end of the narrow chamber are painted six dots – in two parallel rows – just like the ones in the Shaft beside the rhino.

There was an obvious meaning to them, and alongside many repeating symbols throughout the Lascaux cave, they could represent a means of written communication – lost in time. Altogether the Lascaux Cave contains almost 6,000 figures – animals, symbols, and humans.

Today, the Lascaux Cave is completely sealed off – in hopes of preserving the art. Since the 2000s, black fungi was spotted in the caves. Today, only scientific experts are allowed to enter Lascaux and only a day or two per month.

The cave is subject to a strict conservation program, which is currently containing the mold problem. Luckily, the magnificence of the Lascaux Cave can still be experienced in earnest – several life-sized replicas of the cave panels were created. They are the Lascaux II, III, and IV.

Peering beyond the veil of time

Time is merciless. The Earth’s cycle never ceases, and millennia pass and fade away. The purpose of the Lascaux Cave has been lost throughout the millennia. We can never be sure if anything is ritualistic, evocative, or sacrificial.

What we do know is that Paleolithic man’s surroundings were far from primitive. These men were one with nature, well aware of their place in the natural order, and reliant on the blessings that nature provided.

As we ponder this work, we know that the moment has come to reignite the flame of the past and reunite with our most distant ancestors’ lost heritage. And when we encounter these complex, beautiful, and at times scary sights, we are pushed into a world about which we know very little, a world in which we could be completely incorrect.