The Byzantine Empire is best known for its majestic churches, beautiful mosaics, and the preservation of ancient knowledge. However, this empire also played a crucial role in the history of warfare. In particular, the Byzantines developed a new and advanced kind of weapon known as Greek Fire. Although historians still debate exactly how this technology worked, the result was an incendiary weapon that changed warfare forever.

In the early sixth century CE, the Byzantine Empire already existed as a small but growing power in the eastern Mediterranean region. After decades of conflict with their Sassanid rivals to the east and north, however, things were about to get much worse for Constantinople and its inhabitants—they had been methodically attacked by powerful enemy fleets again and again.

In 572 CE, a massive fleet from Constantinople’s arch-nemesis—the Persian Empire—sailed into the Bosphorus Strait and began burning every ship that came its way. The siege lasted two months until finally a courageous local fisherman named Niketas led his fellow fishermen into battle against the enemy ships with pots filled with inflammable liquids that they could throw at their opponents when they got close enough, but remaining in a safe distance. This moment marked one of many turning points in Byzantine history.

A century later, when the first Arab siege of Constantinople began in 674-678 CE, the Byzantines defended the city with the legendary incendiary weapon known as “Greek Fire.” Although the term “Greek fire” has been widely used in English and most other languages since the Crusades, the substance was known by a variety of names in Byzantine sources, including “sea fire” and “liquid fire.”

Greek Fire was primarily used to set fire to enemy ships from a safe distance. The weapon’s ability to burn in water made it especially potent and distinctive because it prevented enemy combatants from smothering the flames during maritime battles.

It’s possible that coming into contact with water exacerbated the flames’ ferocity. It was said that once the mysterious liquid began to burn, it was impossible to extinguish. This lethal weapon helped save the city and give the Byzantine Empire an edge over its enemies for another 500 years.

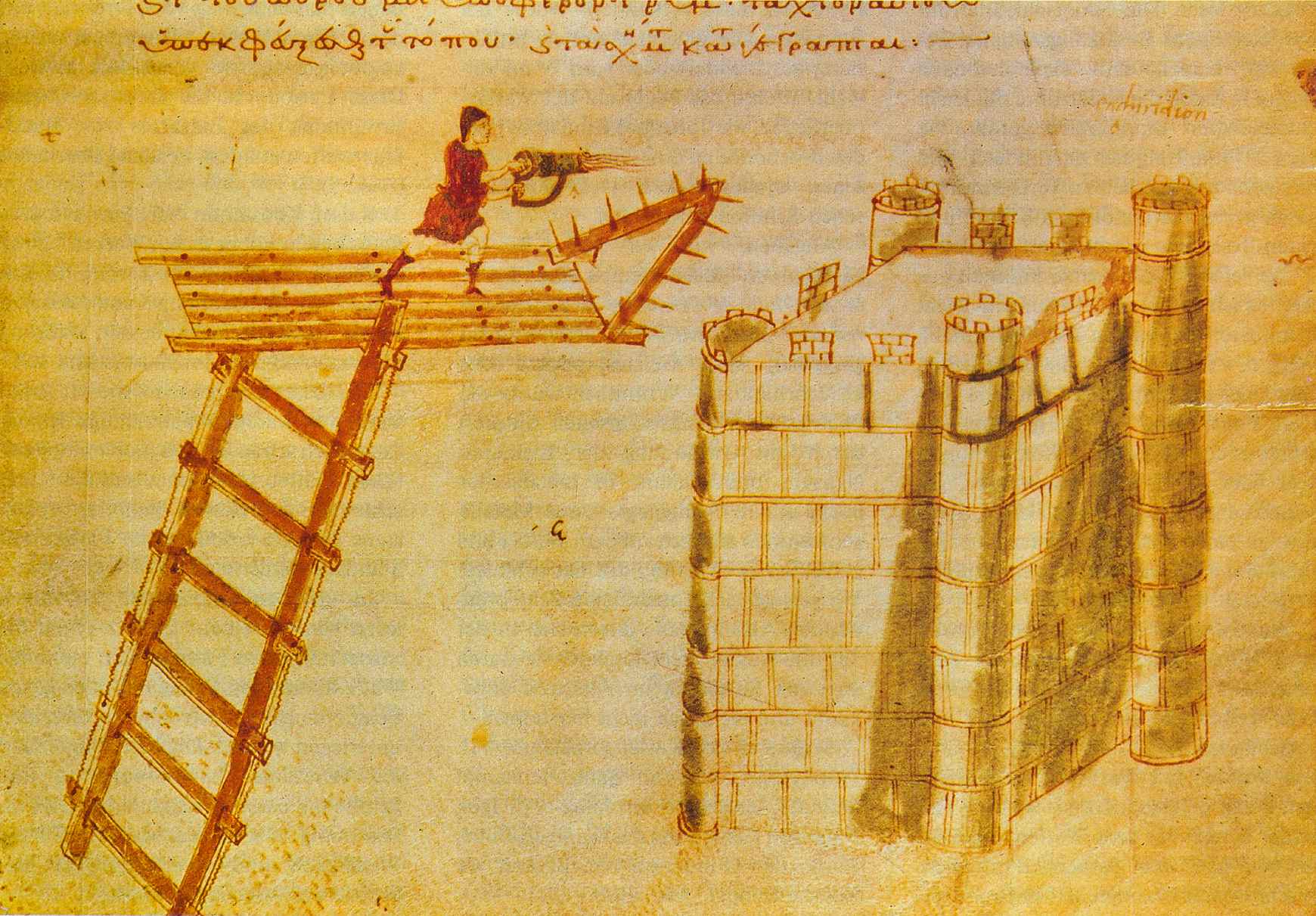

The Byzantines, like modern flamethrowers, are said to have built nozzles or siphn on the fronts of some of their ships to shower Greek fire on enemy ships. To make matters worse, Greek fire was a liquid concoction that stuck to anything it came into contact with, whether it was a ship or human flesh.

Greek Fire was both effective and terrifying. It was said to make a loud roaring sound and a lot of smoke, similar to a dragon’s breath.

Kallinikos of Heliopolis is credited with inventing Greek Fire in the seventh century. According to legend, Kallinikos experimented with various materials before settling on the perfect combination for an incendiary weapon. The formula was then given to the Byzantine emperor.

Because of its devastating potential, the weapon’s formula was closely guarded knowledge. It was only known to the Kallinikos family and Byzantine rulers and was passed down from generation to generation.

Even when opponents obtained Greek Fire, they were unable to replicate the technology, demonstrating the effectiveness of this tactic. However, this is also why the method for producing Greek fire was eventually forgotten by history.

The Byzantines compartmentalized the process of making Greek Fire so that each person involved knew only how to make the specific portion of the recipe for which they were responsible. The system was designed to prevent anyone from knowing the entire recipe.

Byzantine princess and historian Anna Komnene (1083-1153 CE), based on references in Byzantine military manuals, provides a partial description of the recipe for Greek Fire in her book The Alexiad:

“This fire is made by the following arts: From the pine and certain such evergreen trees, inflammable resin is collected. This is rubbed with sulfur and put into tubes of reed, and is blown by men using it with violent and continuous breath. Then in this manner it meets the fire on the tip and catches light and falls like a fiery whirlwind on the faces of the enemies.”

Although it appears to be an important part of the recipe, this historic recipe is incomplete. Modern scientists could easily create something that looked like Greek Fire and had the same properties, but we’d never know if the Byzantines used the same formula.

Like most aspects of Byzantine military technology, the precise details of Greek Fire deployment during the siege of Constantinople are poorly recorded, and subject to conflicting interpretations by modern historians.

The exact nature of Greek Fire is disputed, with suggestions including it being some form of sulfur-based incendiary compound, a flammable petroleum-based substance/naptha, or an aerosolized liquid flammable substance. Whatever the case, Greek Fire was used primarily as a powerful naval weapon, and was very effective in its time.