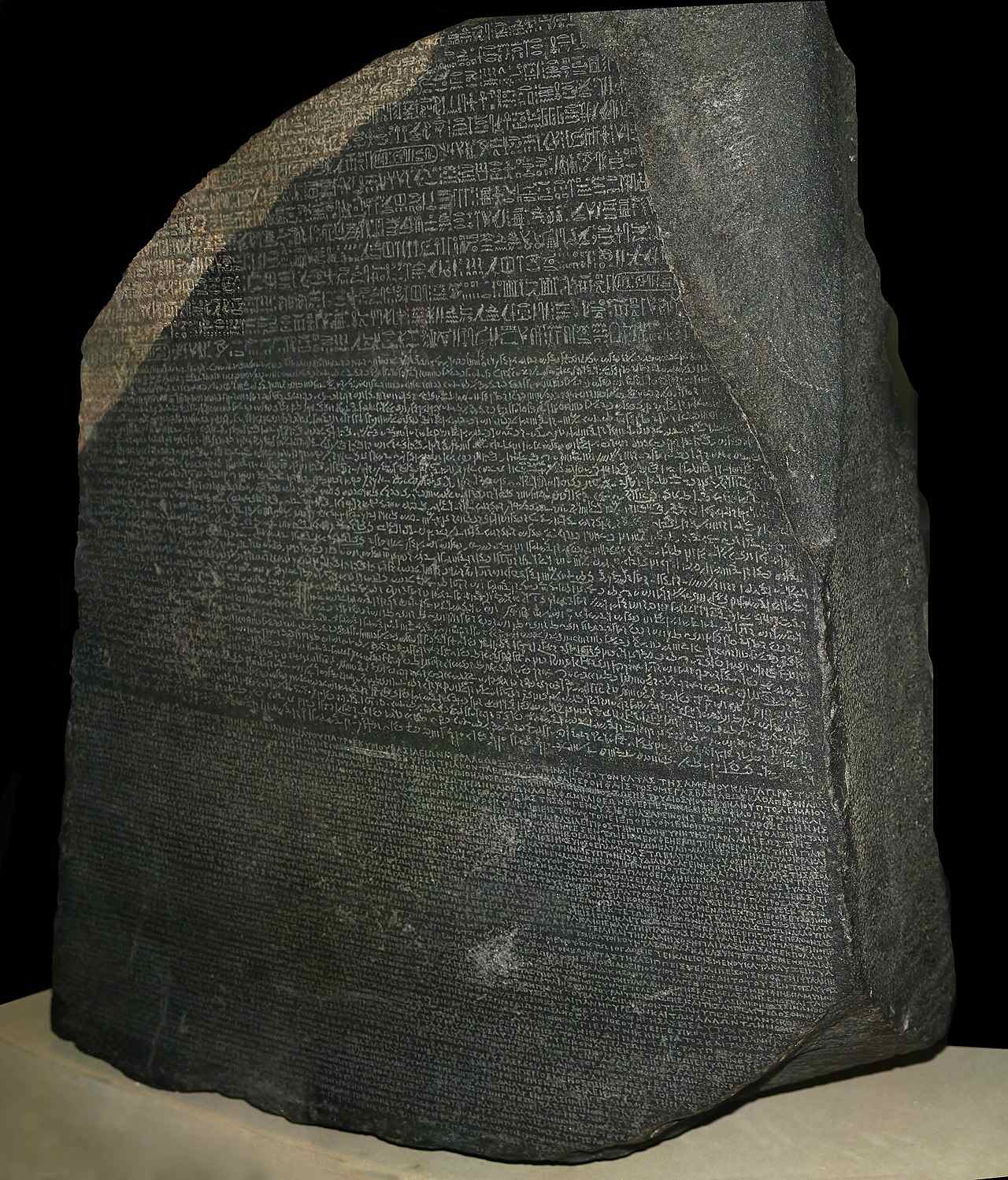

Have you ever wondered how we know so much about ancient Egyptian culture and history? The answer lies in the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799. This lucky find provided the key to unlocking the mystery of Egyptian hieroglyphics, allowing scholars to finally understand the language that had been a mystery for centuries.

The Rosetta Stone translated a Demotic decree, the language of everyday ancient Egyptians, into Greek and hieroglyphics. This groundbreaking discovery opened the door to a wealth of knowledge about the ancient civilization, from their social and political structure to their religious beliefs and daily life. Today, we are able to study and appreciate the rich culture of the Egyptians thanks to the tireless efforts of scholars who deciphered the hieroglyphics on the Rosetta Stone.

Like the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, for years, the linear Elamite script has been a mystery to scholars and historians alike. This ancient writing system, used by the Elamites in what is now modern-day Iran, has confounded researchers for decades with its complex characters and elusive meaning. But recent breakthroughs in deciphering the script have given hope that the secrets of linear Elamite may finally be revealed.

With the help of advanced technology and a dedicated team of experts, new insights into this ancient language are emerging. From clues found in inscriptions and artifacts to advanced computer algorithms, the puzzle of linear Elamite is slowly being pieced together. So, have scholars finally cracked the code?

A team of researchers, with a member each from the University of Tehran, Eastern Kentucky University and the University of Bologna working with another independent researcher, has claimed to have deciphered most of the ancient Iranian language called Linear Elamite. In their paper published in the German language journal Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie, the group describes the work they did to decipher the examples of the ancient language that have been found and provide some examples of the text translated into English.

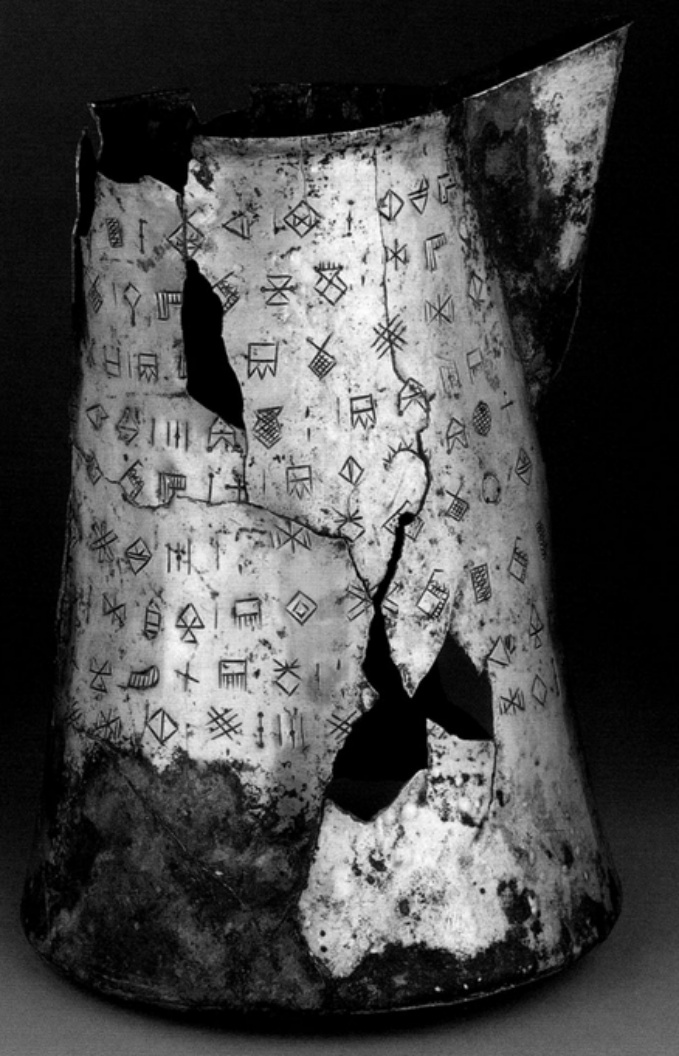

In 1903, a team of French archaeologists unearthed some tablets with words etched onto them at a dig site on the Acropolis mound of Susa in Iran. For many years, historians believed the language used on the tablets was related to another language known as Proto-Elamite. Subsequent research has suggested the link between the two is tenuous at best.

Since the time of the initial find, more objects have been found that were written in the same language—the total number today is approximately 40. Among the finds, most prominent are inscriptions on several silver beakers. Several teams have studied the language and have made some inroads, but the majority of the language has remained a mystery. In this new effort, the researchers picked up where the other research teams left off and also used some new techniques to decipher the script.

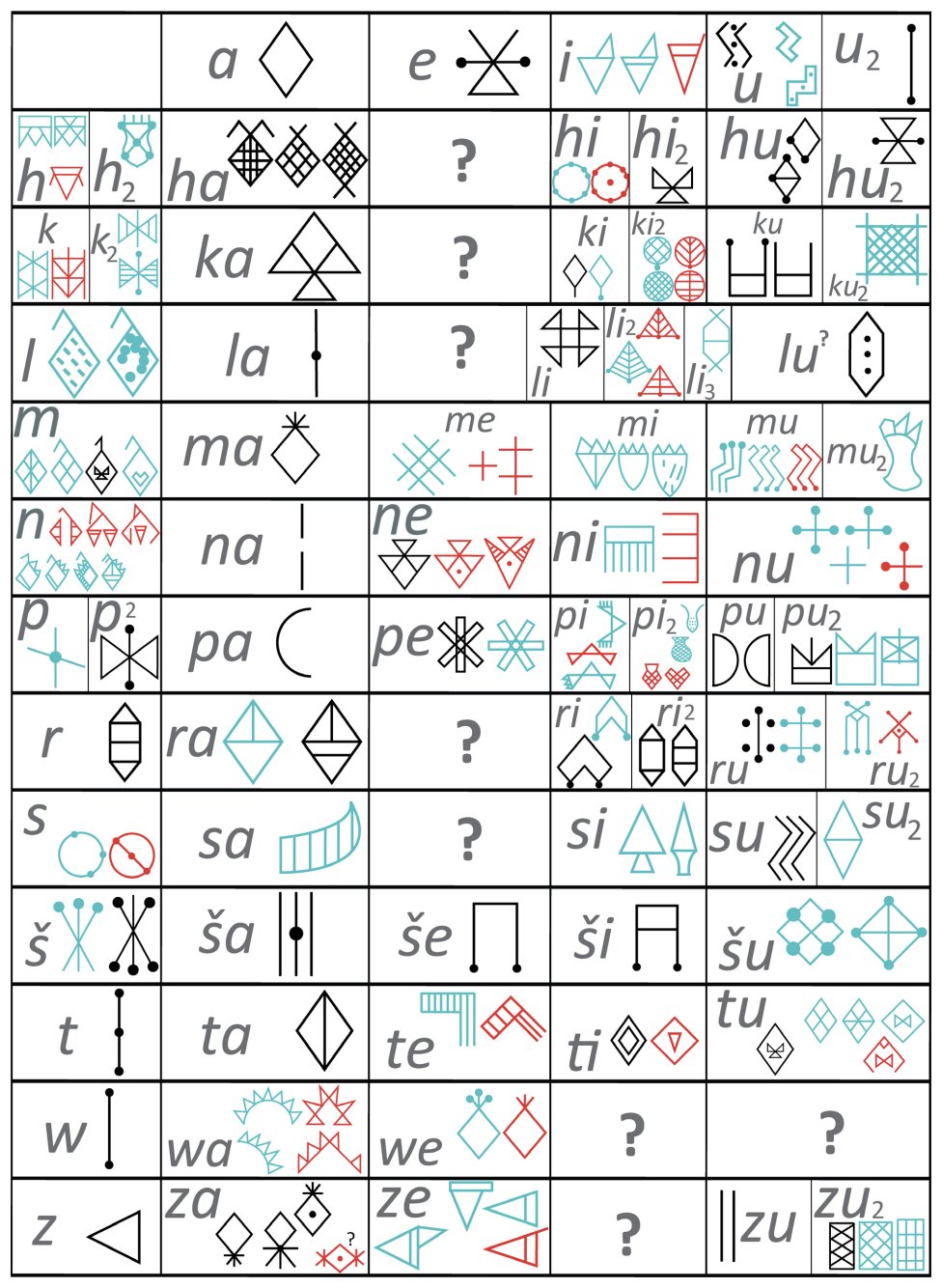

The new techniques used by the team on this new effort, involved comparing some known words in cuneiform with words found in the Linear Elamite script. It is believed that both languages were used in parts of the Middle East at the same time and thus, there should be some shared references such as the names of rulers, titles of people, places or other written works along with common phrases.

The researchers also looked at what they believed to be signs, rather than words, looking to assign meanings to them. Of the 300 signs they were able to identify, the team found they were only able to assign 3.7% of them to meaningful entities. Still, they believe they have deciphered most of the language and have even provided translations for some of the text on the silver beakers. One example, “Puzur-Sušinak, king of Awan, Insušinak [likely a deity] loves him.”

The work by the researchers has been met with some skepticism by others in the community due to a variety of events surrounding the work. Some of the texts used as sources, for example, are themselves suspect. And some of the collections of materials with the language inscriptions on them might have been obtained illegally. Also, the corresponding author on the paper has refused requests to comment on the work done by the team.