A mystery man was hanged by the rope and then ceremoniously beheaded sometime between 673 BC and 482 BC in an area that would one day be known as East Heslington York. His decapitated head was buried immediately after being put face down in a hole. Was this man a criminal who had been sentenced to death by tribal justice, or was he a sacrifice to satisfy their gods?

Ceremonial actions like this were fairly prevalent in Bronze Age and early Iron Age Europe. Both sacrifice and decapitation were performed to please their gods and to instil terror in their adversaries.

The severed heads and dead bodies were also employed as marks for sacred places of water by the ancient Britons and Celts. Later, severed heads were utilised as trophy displays for warriors and leaders alike to retell their combat stories and the grisly acquisition of the sacrificed human gazing at them through their vacant skeletal eyes.

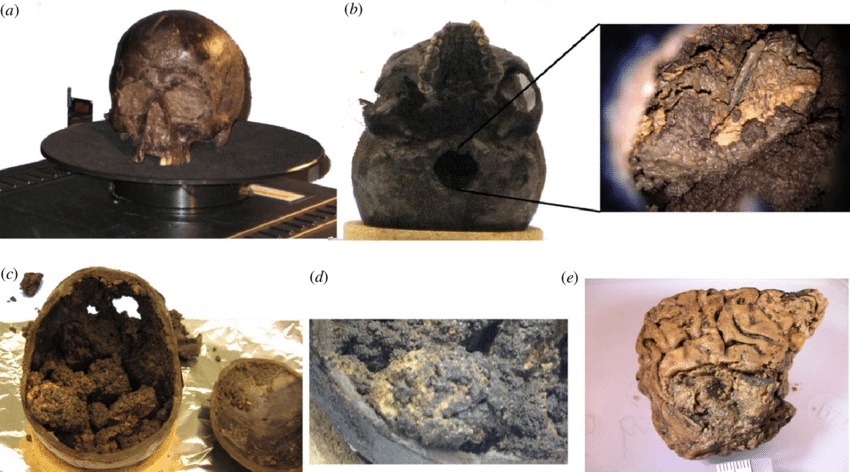

An Iron Age man’s blackened skull was discovered in a flooded trench at site A1, Heslington, North Yorkshire, UK, in 2008. The skull and jaw were discoloured darkly and were lying face down. Excavators thought this individual was the victim of a ceremonial killing.

Though his identity was lost, his remains would astound the archaeological world by displaying his skull, neck, and well-preserved brain. Was the destiny of this guy, who was face down in a wet pit, ceremonial? Why was this person beheaded? And what caused his brain to be preserved?

A brief cultural history of the Heslington Man’s era

Those chosen for sacrifices in Iron Age Britain (800 BC – 100 AD) were either criminals or captives of war. People who were not prisoners of some sort were seldom sacrificed. As with the northern Lindow bog mummies, once these people were sacrificed, the majority of their remains were immersed face down in the water.

In some cases, such as the skull of an Iron Age lady discovered on the banks of the Sowy River in Somerset, archaeologist Richard Bunning believes her death was part of a ceremony, with her skull purposefully put in a watery environment. The ancient Britons believed that most bodies of water were portals into other realms, maybe where the gods lived.

However, only the head of the Heslington man, who was hanged and later beheaded, was buried. Was his case as formal as the others?

According to University of Leicester scholar Ian Armit, the human head had a significant connection with fertility, power, gender, and prestige throughout Iron Age Europe. This ritual was seen in recorded classical literature by evidence of the removal, curation, and exhibition of the head. This has traditionally been connected with a Pan-European “head cult,” which was purportedly utilised in prehistory to support the concept of an united Celtic civilisation (Armit, 2012).

The severed heads of their adversaries were embalmed and displayed by ancient Celts. These prizes were mentioned by the Greek authors Diodorus and Strabo. Both suggested that Celtic warriors used cedar oil to preserve the skulls of their foes.

The Greek sources detailed the ritual traditions of the ceremonial removal of enemy heads killed in combat in the instance of the ancient Celts. They were embalmed and displayed in front of the victor’s home. The sacrificed’s weapons would be laid with the chopped heads.

Several skulls were discovered alongside antique weaponry going back to the 3rd century BC, similar to the archaeological findings made in Le Cailar, France, a 2,500-year-old village on the Rhone River. Le Cailar was a Celtic town where the severed heads were possibly displayed until the region was abandoned about 200 BC.

These heads, according to researchers, were intended for the Celtic inhabitants to stare at in awe. This was in contrast to the traditional idea that severed heads served as warning signs for strangers entering the village. It was revealed that pinaceae oil was applied multiple times in order to preserve the skull.

Though ‘trophy skulls’ were highly valued in Iron Age European civilizations, there was no indication of embalming or smoking in the case of the Heslington skull. So the issue remains: why did his brain survive?

Heslington Brain: Archaeological finding

During the building of the University of York’s new campus in August 2008, Mark Johnson of the York Archaeological Trust discovered a blackened human skull, face down, at the A1 site at Heslington East, York, UK. A limited quantity of animal bone pieces were discovered with this discovery.

Several previous water channels, as well as linear ditches with 2,500-year-old prehistoric dates, were also discovered. Water from springs and seeps along the moraine slope had been channelled into a number of wells, two of which had wicker lining. These exhibited indications of usage from the Bronze Age (2,100 BC – 700 BC) to the Middle Iron Age (800 BC – 150 BC).

Excavations were carried out in the south, where hundreds of trenches showed occupancy waste and suggested at additional ceremonial events that lasted from the Bronze Age to the early Roman period. Many were denoted by single stakes. These holes were made of ‘burned’ cobbles of local stone.

Other items were a decapitated red deer buried in a paleochannel and an unworked red deer antler discovered in an Iron Age ditch. But, of all the discoveries, site A1’s face-down blackened human skull was the most intriguing. It was set on a wet, dark brown organic-rich, soft sandy clay.

The fractures in the skull were caused by a traumatic displacement of the vertebra at the base, according to an examination of the skull. On the frontal side of the centrum, nine horizontal sharp force cut marks created by thin-bladed tools were visible. The cut marks showed that the individual’s head was severed after he or she was hanging.

Further inspection of the cranium revealed a robust mass that was inconsistent with the dark brown clay and silt. When researchers examined the substance via the endocranial cavity through the foramen magnum, they discovered a presence of yellow material, which was later confirmed to be the brain.

As a result of this extraordinary finding, a multidisciplinary team led by Dr. Sonia O’Connor was established to examine the Heslington brain as well as the circumstances that led to its amazing preservation.

Scientific analysis of the Heslington Brain

Further investigation indicated that the skull belonged to a man, according to O’Connor’s team. The age of death was determined to be between 26 and 45 years old based on the examination of the skull suture closures and molar attrition. There was no indication of illness in the skull.

As previously stated, an examination of the two adjacent vertebrae revealed a broken arch of the second column on either side, resulting in what looked to be traumatic spondylolisthesis, most likely induced by hanging. Nine strong tool cut marks were also discovered between two vertebrae, indicating that the skull had been meticulously detached after death.

The brain matter in the skull had decreased but was still discernible. Although the surface morphology of the organ was intact and intermixed with layers of mixed silt, its preservation was attributed to a number of reasons, including the location of the severed head.

The anoxic soil in the wet hole deprived the earth of oxygen. Another aspect was that the Heslington brain had experienced chemical alterations as well as the circumstances it was subjected to while buried. There were no indications of adipocere or fatty compound tissue degradation.

This meant that the head was buried quickly after decapitation, with no time for decomposition to occur. Another aspect is that, in most cases, bacteria swarm from the stomach and travel throughout the body via blood vessels during the decay process. Because the skull had been cut and blood had been drained, there was no way for the germs to infect it.

Heslington Man’s DNA results

During the course of the investigation, the researchers also took a DNA sample from the Heslington brain. The individual’s DNA sequencing revealed a close match to Haplogroup J1d, which was initially discovered in individuals from Tuscany and to the Near East.

This DNA sequence group has not yet been discovered in the British population; nevertheless, additional sampling of the British population may show more people who belong to this haplogroup. O’Connor also speculates that this group existed in Britain in the past and may have vanished due to genetic drift.

Despite the fact that considerable information about this person has been uncovered via archaeological and forensic research, the primary questions concerning his death remain unanswered. Why was he chosen, and why was his head put in the grave so quickly?

The study of the Heslington Brain continues

The investigation into the Heslington Man continues. Though the major studies of the time, death, and probable group this individual belonged to have finished, and subsequent investigations will continue indefinitely, many questions remain, such as why this guy was slain. In many other examples of severed heads, they were either battle trophies or ritual sacrifices meant to please the gods.

Historically, the Celts have been known to decapitate prisoners of war and flaunt their severed heads. This method also necessitated the continual preservation of these skulls through the use of embalming fluids. Archaeologist Rejane Roure of the Paul Valery University of Montpellier in France established this theory.

Roure and her colleagues studied skull fragments discovered at Le Cailar, a fortified Celtic hamlet in southern France. Signatures of resin and plant oils were discovered in her chemical study of the Le Cailar skull pieces. In addition, cutmarks indicated that the brains had been removed.

There was no evidence of embalming or smoking on the Heslington skull. The skull was removed and buried quickly, implying that this individual was not killed in combat or thought worthy of exhibition. Another truth is that the brain was not only present in the skull, but it was also very well maintained by natural events.

In other cases, bodies and heads would be buried face down by watery areas said to represent portals to other worlds. The Heslington skull, like the previous instance with Bunning’s study of the Iron Age lady discovered on the banks of the Sowy River in Somerset, was discovered face down in a wet hole. His location might portend such a catastrophe.

According to Greek and Roman historical records, the ancient people of Britain thought that natural pools of water were portals into other realms and hence required human sacrifice to deliver their gifts to the gods.

However, as writer Riley Winters points out in her piece on Iron Age Britain, the only source we have about sacrifice is in fragments written by Greek and Roman historians; Romans with a hostile attitude toward Britons like Julius Caesar, Luncan, and Tacitus.

Despite their disdain for the ancient British, their stories are the only ones that detail the ceremonial burnings, hanging, stabbing, throat-cutting, and a number of other techniques used in human sacrifice.

With these data in hand, one can build a more vivid image of the Heslington man’s final days. The man from Heslington may have been an outsider who was apprehended. The Celts would have thought him worthy of holy sacrifice as they completed work diverting streams and canals for their wells.

He may have been blessed by a priest at this ritual, just before being taken to a tree and hung till he died. Once his life had ended, he would have been lowered from the tree and his head severed from his body as others laboured to dig a pit. His head would then be properly positioned downward in preparation for his ceremonial entrance into the other dimension.

If only the ancient Celts had known that the enigmatic Heslington man’s thoughts would be preserved until modern scientists found his brain, ultimately putting him to rest. But we’ll never know if this was true. Hopefully, additional research will uncover more about the Heslington brain’s history.