In 2008, a cuneiform clay tablet ― that puzzled scholars for over 150 years ― was translated for the first time. The tablet is now known to be a contemporary Sumerian observation of an asteroid impact at Köfels, Austria. But there is no crater in Köfels territory, so to modern eyes it does not look like an impact site should actually look, and the Köfels event remains hypothetical to this day. Therefore, the clear evidence in the cuneiform clay tablet that puzzled the earlier researchers remains shrouded in mystery!

The Sumerian Planisphere – a forgotten Star Map

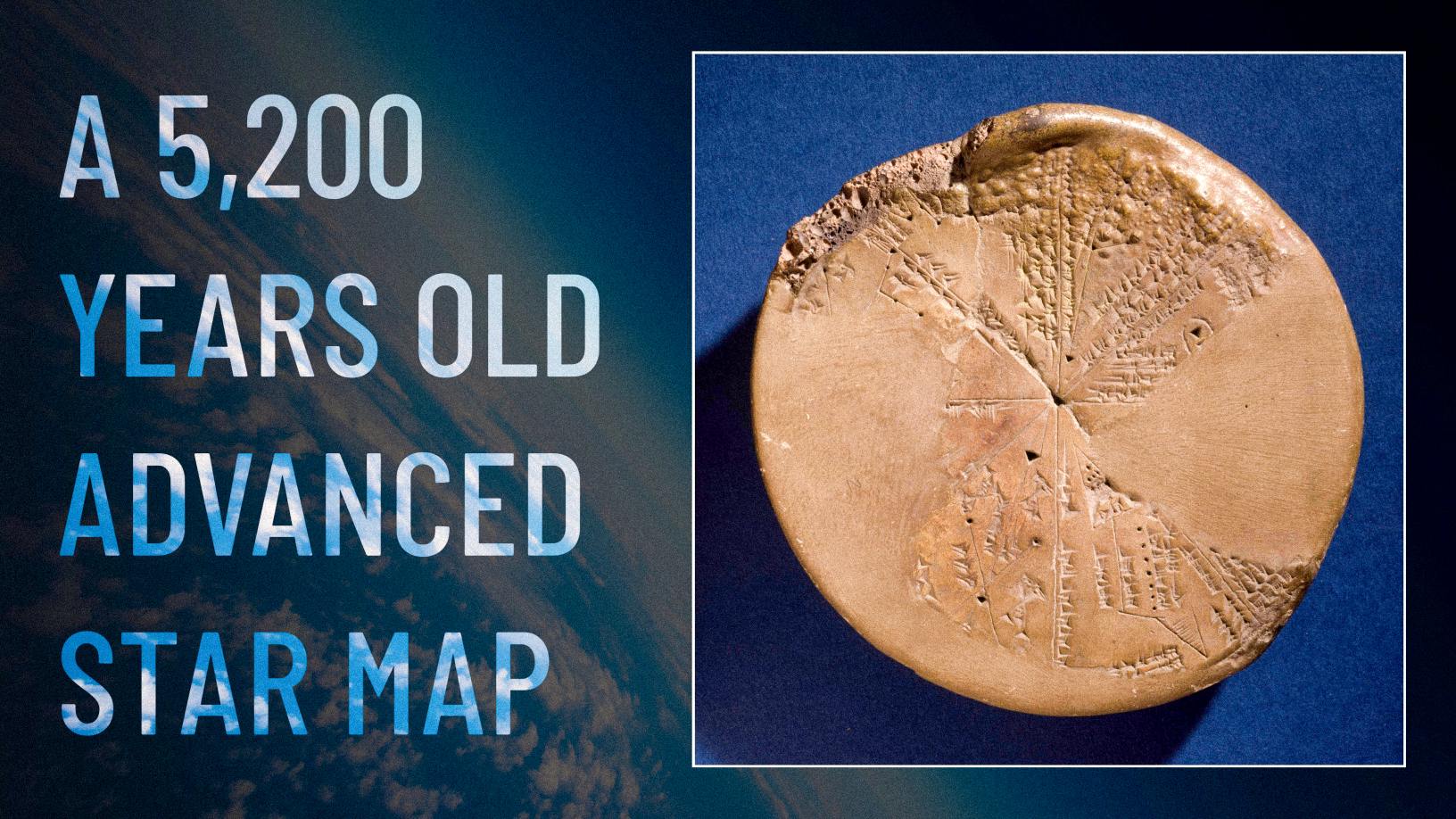

In the late 19th century, a strange-looking circular stone-cast tablet was recovered from the 650 BC underground library of King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, Iraq, by Henry Layard. Long thought to be an Assyrian tablet, computer analysis has matched it with the sky above Mesopotamia in 3,300 BC and has proved it to be much more ancient of Sumerian origin.

For over 150 years scientists have tried to solve the mystery of this controversial cuneiform clay tablet which indicates the so-called Köfel’s impact event was observed by Sumerians in ancient times. It was a phenomenal incident where a kilometer-long asteroid crashed into the Alps, near Köfels, Austria over 5,600 years ago.

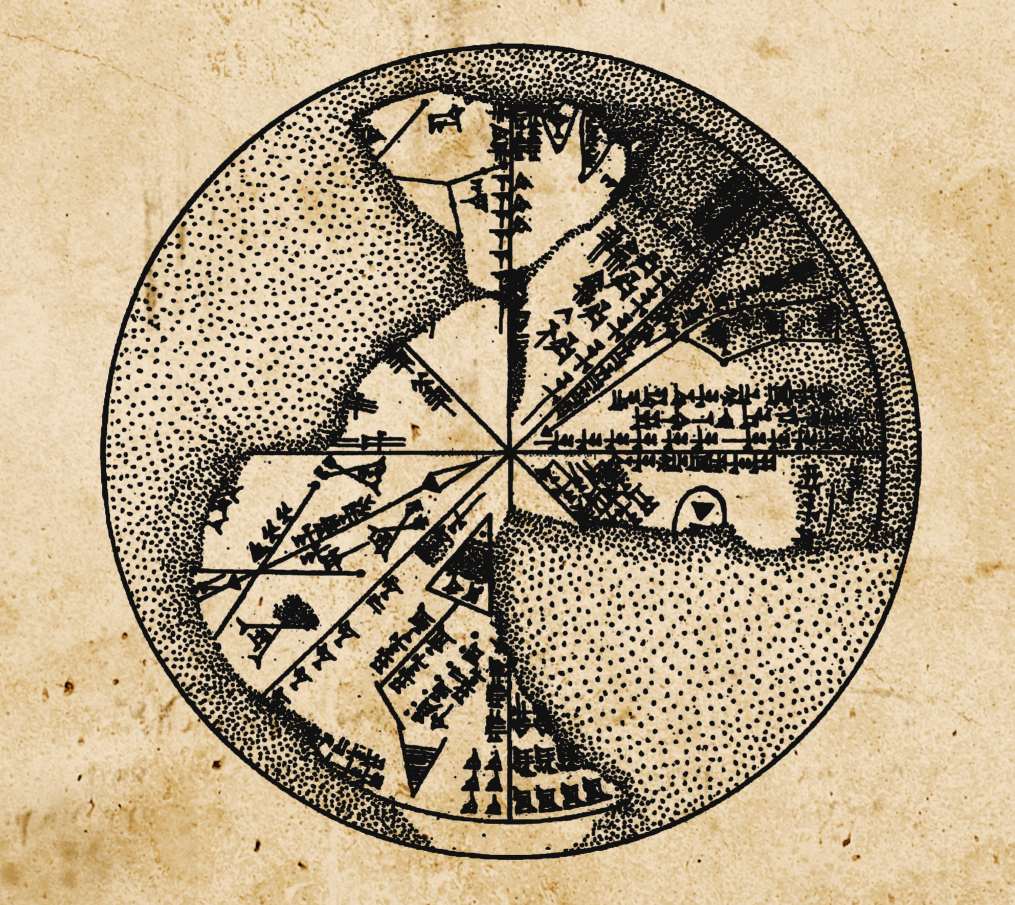

The tablet is an “Astrolabe,” the earliest known astronomical instrument. It consists of a segmented, disk-shaped star chart with marked units of angle measure inscribed upon the rim. Unfortunately, considerable parts (approximately 40%) of the planisphere on this tablet are missing, damage which dates to the sacking of Nineveh. The reverse of the tablet is not inscribed.

The ancient Sumerian civilization may have been underdeveloped in the sense of a written script, for example, but they sure understood astronomy and the night sky to a certain extent. And this is evident from this 5600-year-old Sumerian Star Map.

Still under study by modern scholars, the cuneiform tablet in the British Museum collection No K8538 ― known as “the Planisphere” ― provides extraordinary proof for the existence of sophisticated Sumerian astronomy.

10 interesting facts about the Sumerian Planisphere

Though it was discovered more than 150 years ago, the Sumerian Planisphere has been translated only a decade ago, revealing the oldest documented observation of an extraterrestrial object that came from space and landed on the Earth’s surface ― a comet. Here, in this article, are some of the most important facts about this ancient Sumerian Star Map.

1 | The exact date of the comet’s impact

The tablet’s inscriptions provide an exact date and time for the supposed meteor’s impact on the Earth: June 29, 3123 BC, according to the writings.

2 | The ruins of the Royal Library of King Ashurbanipal held 20,000 more tablets including the Sumerian Planisphere

More than 20,000 antique tablets were unearthed by archaeologists when excavating the ancient site of the city of Nineveh, which took several years to complete. The “Planisphere,” which is the one we are talking about today, is widely believed to be the most difficult to interpret. Fortunately, 150 years later, the remaining inscriptions were translated, revealing a wealth of information that was previously unknown.

3 | The Planisphere is an exact copy of the original one

Researchers believe that the Planisphere is an identical replica of an older original tablet created by an astronomer and observer of the actual event during his lifetime.

4 | An eight-picture series depicts the entire event, from the appearance of the comet to its eventual impact

Despite its diminutive size (approximately 14 centimeters in diameter), the Sumerian Star Map tablet masterfully depicts the course of events by dividing it into eight pieces or pictures. About half of the inscriptions were destroyed over time, but the portions that were left could still be translated using current technology. Despite its modest size and surface, the creator of the tablet managed to convey an astonishing amount of information about the observation and its implications.

5 | There are illustrations of constellations and their reasonable names on the Sumerian Star Map

No matter how undeveloped we think our ancient ancestors were, but the fact is that they had a superior understanding of the night sky and the constellations beyond our imaginations. There are constellation illustrations on the Planisphere, along with their names and where they are in relation to the comet’s path of travel precisely. The third image, for example, reveals that the comet passed through Orion on the 9th day of the observance.

6 | The ancient astronomer used impressively accurate trigonometrical measurements

The ancient astronomer possessed an excellent understanding of trigonometry and was able to record the comet’s flight path, time of arrival, and distance traveled from the moment it first appeared in the sky.

7 | The first five pictures describe the 20 days of astronomical observance

It has already been mentioned that the tablet is divided into eight pieces or images, which are displayed in a sequential fashion. It is important to note that the data presented in this order, from first to fifth, comprises observations from the first astronomical sighting until the end of day 20 prior to the impact of the twenty-first day. Thus, the comet is depicted in these five photographs while it was visible above the horizon.

8 | The sixth and the seventh pictures explain the impact and its aftereffect

Although the observer did not witness the impact from a close distance since it would have meant the end of his life, he did describe flash lighting in the sky and the massive rise of ash plumes as a result of the collision, which was recorded on the tablet. In summation, the seventh image captures the entirety of the events that occurred during the night following the meteor fall. Beyond the horizon, red hot-glowing ash and dust plume columns rise to the surface of the water, visible in the darkness.

9 | The eighth picture, which is the final shot, includes the calculation of the comet’s travel path

The ancient astronomer did not conclude his observations until he had made accurate estimations of the comet’s travel path before it collided with the Earth. It was on the 21st day of observation after which the eighth picture was created after the impact. There are four observations of the comet’s flight taken in daylight just before the impact crash shown in this picture. Remarkably, the entire sequence of data written on the tablet is more than astounding, especially considering that the entire collection of observations were made more than 5,200 years ago.

10 | The comet described on the Sumerian Star Map may have brought the end to several ancient civilizations

Meteors have been responsible for the extinction of life on Earth on numerous occasions throughout history, and scientists speculate that this comet may have had a significant impact on life in the ancient world. More specifically, the ancient city of Akkad, which archaeologists have not yet been able to locate, could have been completely destroyed by a comet impact. Though the exact location of this fabled city from antiquity is still unknown, however, it is possible that it was destroyed because it was so close to the impact zone. The comet simply wiped everything off.

Could the Tablet K8535 be the answer to a giant mysterious landslide at Köfels?

The giant landslide centred at Köfels in Austria is 500 metre thick and five kilometres in diameter and has long been a mystery since geologists first looked at it in the late 19th century. The conclusion drawn by research in the middle 20th century was that it must be due to a very large meteor impact because of the evidence of crushing pressures and explosions.

But this view lost favour as a much better understanding of impact sites developed in the late 20th century. However, the distinct evidence inscribed on the Sumerian Planisphere K8535 tablet brings the impact theory back into play. Isn’t it?

Conclusion

The K8535 tablet is a late Babylonian copy of an early Sumerian astronomical tablet. The original document, regarded of maximum importance, was copied over more than 2,500 years.

The observed comet passed the Pleiades, Aldebaran, moved further towards Orion and finally crashed into the highly advanced, irrigation-based agricultural civilization of Akkad and Sumer, in 3123 BC, destroying the entire Akkadian empire and its capital city of Agade.

About 40% of the tablet is missing. Fortunately, the entire flight path of the comet is preserved. Broken-off sections mostly deal with observations concerning the impact itself and with the immediate impact aftermath, recording what could be seen from the observation tower, looking towards the crash site. The information is adequate to reconstruct the detailed comet advance and the impact process sequence.

The K8538 witness account must be considered as part of a great number of preserved “Mesopotamian city laments”, which report the end of Akkad and Sumer by an enormous atmospherical tempest.

These laments were rehearsed on stage in public over millennia, accompanied with drummer background. Their poetical lamentation style misled various contemporary assyriologists to opine that those documents are nothing but entertaining poetical and mystical fiction, and that there had never been a destructive tempest in Sumer, disregarding observations of hundreds of historical witnesses.

The K8538 observation tablet was made by an unknown alert Sumerian astronomer, who sensed the historical significance of the event on his astronomical lookout tower and decided to document it. The authors Bond and Hempsell gave him the name “Lugalansheigibar – the great man who observed the sky.”

His trigonometrical observations witness the comet approach and its terrestrial impact. For this reason, K8538 was guarded, restored and copied over the millennia. The tablet demonstrates the high level of science and astronomy reached four thousand years ago.

Today, the real value of K8538 is not only confined to history. It is also of immense value for today and the future of humankind as well, because it holds in it a unique and accurate precedence observation of a disastrous cosmic asteroid, impacting Earth.