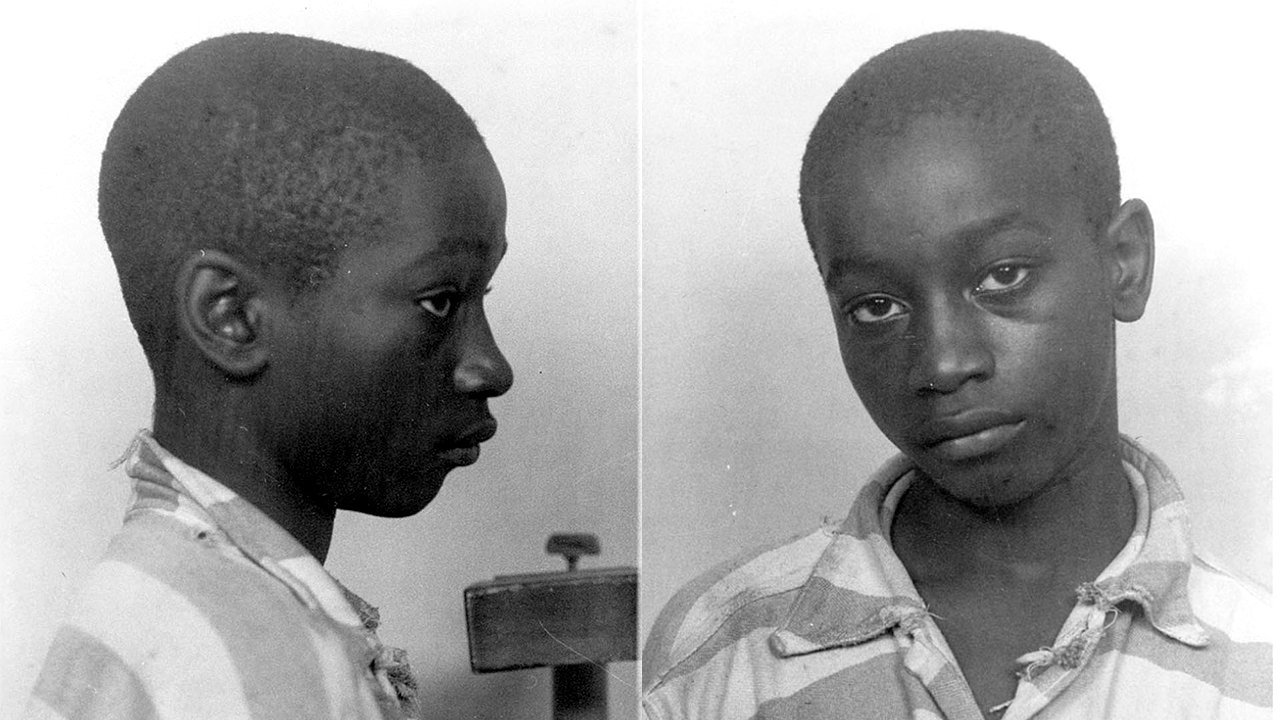

George Stinney Jr. – racial justice to a black boy executed in 1944

Fourteen-year-old George stinney Jr. is the youngest person to be sentenced to death and executed in modern history. He always carried a bible in his hands, claiming to be innocent. The same Bible was used as a seat booster as he was so small for the electrocution chair. He was convicted of killing two white girls. All the jury members in the trial were white, the trial lasted only two hours. Before his execution, he spent 81 days in prison without seeing his family. Seventy years later his innocence was proven by a judge in South Carolina. Is this called justice??

George Stinney Jr. – A Victim Of The Racial Justice:

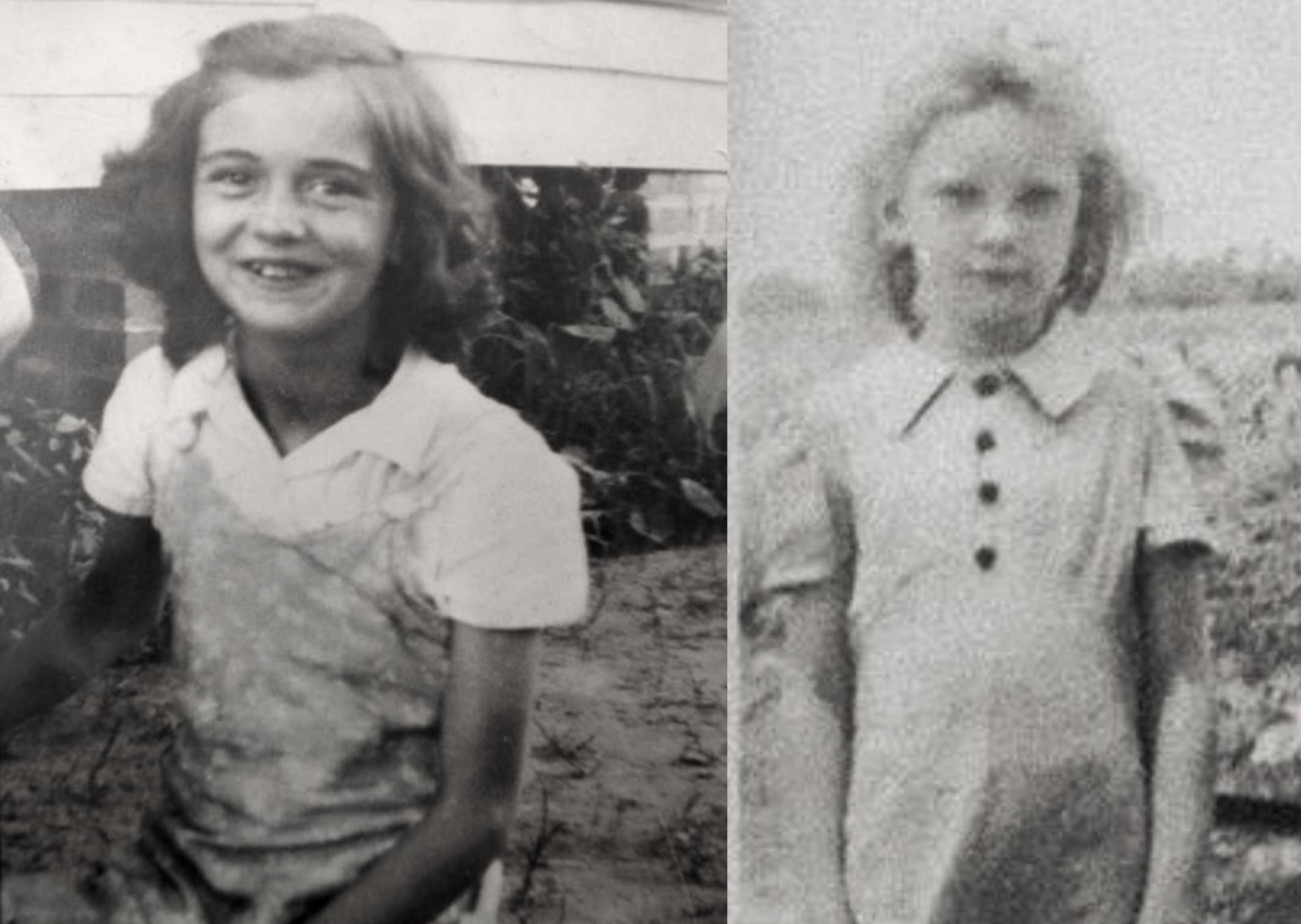

On June 16, 1944, George Junius Stinney Jr., a ninety-pound, black, fourteen-year-old boy, was executed in the electric chair in Columbia, South Carolina, the United States. Three months earlier, on March 24, George and his sister were playing in their yard when two young white girls named Betty June and Mary Emma, ages 11 and 7, briefly approached and asked where they could find maypop flowers. Hours later, the girls failed to return home and a search party was organized to find them.

George Joined The Search Party:

George joined the search party and casually mentioned to a bystander that he had seen the girls earlier. The following morning, their dead bodies were found in a shallow ditch on property owned by George Burke Sr., George Stinney’s father who led the search party.

The Crime Scene:

The girls’ bodies were stiff when the preacher’s boy found them in a shallow, waterlogged ditch in the woods. They were on their backs, like a pair of discarded dolls, bruised and broken beyond repair. On top of them lay a bicycle, its front wheel gone from the frame.

There were no signs of a struggle when Dr. Asbury Cecil Bozard examined the bodies, but it was clear they’d met cruel and violent ends. Mary Emma had a jagged, two-inch-long cut above her right eyebrow and a hole boring straight through her forehead into her skull. Betty June suffered at least seven blows to the head, so punishing, the doctor noted, the back of her skull was “nothing but a mass of crushed bones.”

Nothing like this had ever happened in Alcolu, a sawmill village along the northern hill of the Pocotaglio Swamp in rural Clarendon County.

George Was Arrested:

George Stinney’s mother was a cook at Alcolu’s school for black children and his father, George Sr., a former sharecropper, worked for the mill. They were poor, but they were fed and clothed, and spending a peaceful life.

That afternoon, George and Amie were home with their half-brother, Johnny, who was visiting from their grandmother’s house in the nearby town of Pinewood before reporting for military duty. Their parents were away, and their brother Charles had gone with their sister Katherine to the beauty parlour.

Amie, who was 8, played in the yard with a young brood of Rhode Island Red hens as a pair of black cars drove up their street. She watched as white men in suits stepped out of them and walked into the house through the backdoor. Amie hid in the chicken coop as they hauled George and Johnny away in handcuffs.

George, she cried, why you leaving me? George hollered back. Go get Kat and Charles! And get Ma!

Then George disappeared into one of the black cars. It was the last time she saw her brother alive.

A Fishy Confession!!

George was arrested for the murders of Betty June and Mary Emma and subjected to hours of interrogation without his parents or an attorney. The Clarendon Deputy Sheriff H.S. Newman told the newspaper that within 40 minutes of his arrest, George had confessed to the murders, though no written or signed statement was presented.

Newman added that George fatally struck them after they resisted his sexual advances. When they threatened to tell their parents, George picked up a foot-long railroad trestle spike and attacked the younger girl first, bashing her several times on the head before turning his weapon on the other.

Crowd Is A Headless Monster:

George’s father was fired from his job and his family forced to flee amidst threats on their lives. The family helplessly fled to their grandmother’s house in Pinewood, taking with them just a few things and leaving the rest behind. On March 26, a mob attempted to lynch George but he had already been moved to an out-of-town jail.

An Unjust Trial:

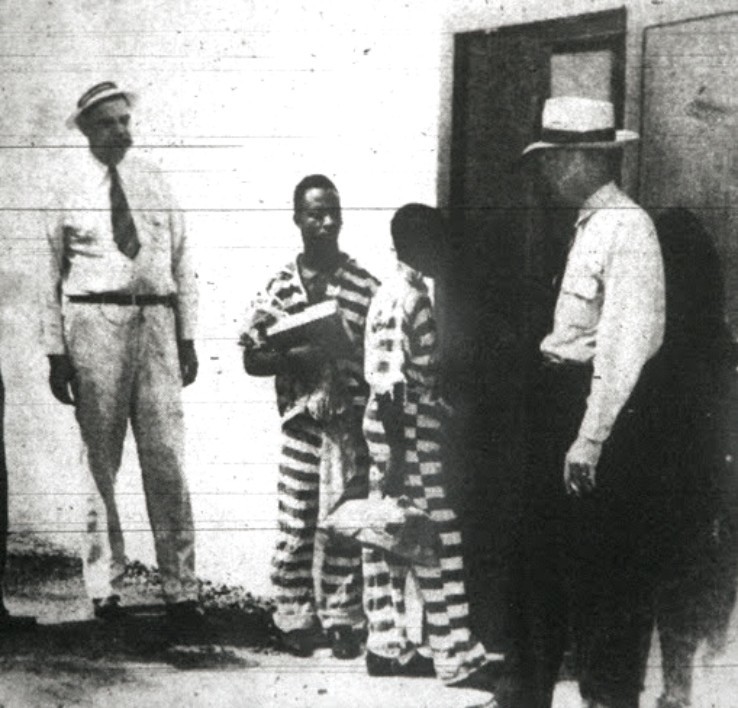

On April 24, George Stinney faced a sham trial virtually alone. No African Americans were allowed inside the courthouse and his court-appointed attorney, a tax lawyer with political aspirations, failed to call a single witness. The prosecution presented the sheriff’s testimony regarding George’s alleged confession as the only evidence of his guilt.

Injustice Rained:

An all-white jury deliberated for ten minutes before convicting George Stinney of rape and murder. They found him guilty with no recommendation for mercy. Judge P.H. Stoll of Kingstree handed down the fourteen-year-old’s sentence immediately: Death by electrocution.

Despite appeals from black advocacy groups, Governor Olin Johnston refused to intervene. George Stinney remains the youngest person executed in the United States in the twentieth century.

The Truth Never Be Hidden Behind Lies:

Sixty years later in 2004, George Frierson, a local historian who grew up in Alcolu, started researching the case after reading a newspaper article about it. He uncovered a number of things proving George Stinney’s innocence. His work gained the attention of South Carolina lawyers Steve McKenzie and Matt Burgess.

McKenzie and Burgess, along with attorney Ray Chandler representing Stinney’s family, filed a motion for a new trial on October 25, 2013.

New evidence in the court hearing in January 2014 included testimony by Stinney’s siblings that he was with them at the time of the murders. In addition, an affidavit was introduced from the “Reverend Francis Batson, who found the girls and pulled them from the water-filled ditch. In his statement he recalls there was not much blood in or around the ditch, suggesting that they may have been killed elsewhere and moved.” Wilford “Johnny” Hunter, who was in prison with Stinney, “testified that the teenager told him he had been made to confess” and always maintained his innocence.

In December 2014, a South Carolina judge Carmen Mullen held a two-day hearing, which included testimony from three of George’s surviving siblings, members of the search party, and several experts. The state argued at the hearing that – despite all the unfairness in this case – George’s conviction should stand.

The trial court disagreed and vacated the conviction, finding that George Stinney was fundamentally deprived of due process throughout the proceedings against him, that the alleged confession “simply cannot be said to be known and voluntary,” that the court-appointed attorney “did little to nothing” to defend George, and that his representation was “the essence of being ineffective.” The judge concluded: “I can think of no greater injustice.”

Final Days Of George Stinney Jr:

Seventeen-year-old Wilford “Johnny” Hunter got arrested for joyriding in a stolen car with a couple of friends in Sumter, about 35 miles away. The ensuing police chase left Hunter with a bullet in his abdomen and a stint at Sumter’s Tuomey Hospital in grave condition.

When he recovered, he wound up at the “big jail” in Sumter with George, who arrived looking frail and underfed.

Hey kid, Hunter asked, What they got you for? They’re going to electrocute me ―George replied.

Shocked, Hunter steadied himself on a bench. Over the course of three days, George found a friend and confidante in the wounded man. To Hunter, George was “the kid,” who liked to sing country songs from The Grand Ole Opry — one favourite was Ernest Tubb’s “Walking the Floor Over You” — and play hide-and-seek in the bunks.

Once, George told him, Johnny, when they electrocute me, I’m coming back and I’m gonna haunt you!

Hunter told George not to talk like that. George asked Hunter to write a letter to a preacher in Florida named S.P. Rewell, whom George said had helped his brother back when he was in trouble. Hunter did so on a penny postcard, telling him it was “a matter of life or death.”

Johnny, why do they want to kill me for something I didn’t do? Why?

Hunter couldn’t answer him. Keys rattled then. A gate creaked open. Heavy footsteps plodded up the stairs. George grew quiet. It was their last day together. George grabbed Hunter, and Hunter flung his arms around the boy.

George whispered: Bye.

One Crime Three Victims: Who Really Killed Betty June Binnicker And Mary Emma Thames??

George Frierson stated in interviews that “there has been a person that has been named as being the culprit, who is now deceased. And it was said by the family that there was a deathbed confession.” Frierson said that the rumoured culprit came from a well-known, prominent white family. A member, or members of that family, had served on the initial coroner’s inquest jury which had recommended that George Stinney Jr. be prosecuted.

Another source says, Frierson asserted that he knew who really killed Betty June and Mary Emma but he would not name the person because he thought it would be considered defamation. He said that the guy was a truck driver and everyone in the community knew who he was.

The Burial Sites Of The Three Victims:

11-year-old Betty June was buried in the Smoak Family Cemetery, Cordova, Orangeburg County, South Carolina.

7-year-old Mary Emma was buried in the Liberty Freewill Baptist Church Cemetery, Manning, Clarendon County, South Carolina.

And 14-year-old George Stinney Jr. was buried in the Calvary Baptist Church Cemetery, Paxville, Clarendon County, South Carolina, USA.

Conclusion:

Through the whole investigation and prosecution of the case, not that anyone with much power seemed to care for George Stinney. He was poor and black. A depraved child-killer to his executioners. A savage rapist to the governor. An unrepentant predator in the press. In the end, a few flimsy imaginations from hatred pushed little George to the brink of death!